The South Korean Air Force was formed in 1949 with no combat aircraft available. Soon after the Korean War broke out on 25 June 1950, the South Koreans received their first 10 F-51 Mustang fighter planes and were forced to train and become effective combat pilots while under fire. The fledgling tiny air force fought for its existence during the first months of the war. By the time the armistice was sign on 27 July 1953, the South Korean Air Force had a full F-51 fighter wing, a training wing, and an aerial reconnaissance unit.

One could say that the US inadvertently created South Korea. At the Tehran Conference in November 1943 and the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Soviet Union agreed to join its allies in the Pacific War within three months after the victory in Europe. Germany officially surrendered on 8 May 1945, and the USSR declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria on 8 August 1945, three months later. This was two days after the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and on August 9 the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. By August 10, the Soviet Army had begun to occupy northern Korea. On the night of 10 August in Washington, US Colonels Dean Rusk and Charles H. Bonesteel III were assigned to divide Korea into Soviet and US occupation zones and they proposed the 38th Parallel as the dividing line. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin maintained his wartime policy of co-operation, and on August 16 the Soviet Army halted at the 38th Parallel for three weeks to await the arrival of US forces from the south.

After the end of WWII on 10 August 1946, the South Korean Air Construction Association was founded to form an Air Force and the first air unit was formed on 5 May 1948. On 13 September 1949, the US contributed ten light observation planes to the South Korean air unit. An Army Air Academy was founded in January 1949. The withdrawal of US forces from South Korea in June 1949 left the south defended by a weak South Korean government. The Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) was officially founded in October of 1949.

In 1949, the Soviet Union shipped 145 WWII era propeller aircraft to North Korea which included La-9s, Il-10s, Yak-3s, Yak-7Bs and Yak-9s. The Soviets considered these planes obsolete since at the time they were re-equipping their air force with new jet fighters which included MiG-9s and Yak-23s. North Koreans were selected for military flight training and the new North Korean Air Force was modeled on the Soviet Air Force.

In early 1950, a US style roundel was adopted. The Yin-Yang in red-blue (with white separation) with white bars bordered blue and red central strip. The word taegeuk refers to the South Korean version of the “yin and yang” symbol, the red-and-blue circle at the center of the South Korean insignia. In Korea, the “yin and yang” are called eum and yang. The taegeuk symbol denotes the concept of “unity of opposites.” The symbol was chosen for the design of the Korean national flag in the 1880s.

Korean War

At dawn on Sunday, 25 June 1950, the North Koreans crossed the 38th Parallel and invaded South Korea. The North Korean Army was supported by Soviet Built T-34/85 tanks and SU-76 assault guns with the North Korean Air Force providing air support. The ROKAF at that time had only 64 rated pilots and consisted of eight Piper L-4 Grasshoppers, four Stinson L-5 Sentinels liaison-type aircraft and ten North American T-6A Texan advanced trainers which were purchased from Canada.

The ROKAF pilots fought valiantly during the first three days of the invasion. Operating from Yoido Air Base near Seoul, the ROKAF flew 123 bombing sorties, dropping 500 hand grenades and 274 Korean-made 15 kilogram (33 lbs) bombs by hand or from improvised bomb racks on the invading North Korean forces. In addition, they flew 165 reconnaissance and liaison sorties during those three days.

After their munitions were used up on June 28, the remaining ROKAF aircraft withdrew from their original air bases near Seoul. During the first days of the war, the ROKAF lost approximately 2/3 of its aircraft, being reduced to two L-4s, two L-5s, and seven T-6As.

A Korean ground crewman hand prop starts a L-4 Grasshopper light observation plane.

Dean Hess

Dean Elmer Hess (6 December 1917 to 2 March 2015) was born and raised in Marietta, Ohio. Hess had began preaching at the early age of 16. He attended Marietta College, Ohio, in the class of 1941. At Marietta College, Hess was accepted into a civilian pilot training program and received his pilot’s license. After graduation, he was ordained as a Pastor in the Disciples of Christ Church in Cleveland, Ohio. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, Hess enlisted in the US Army Air Forces Aviation Cadet Program and became a flight instructor at Napier Field, Alabama.

After numerous rejected requests, Hess was finally transferred to France in September 1944 and was assigned to the 511th Fighter Squadron, 405th Fighter Group, US 9th Air Force based at Saint-Dizier air base (east of Paris and southeast of Reims). He flew Republic P-47D Thunderbolts with squadron code K4 and the squadron colors were yellow leading edge of the engine cowling, yellow canopy frame and a yellow horizontal tail band above the serial number. On 8 February 1945, the 511th Squadron relocated from Saint-Dizier to Asch airfield (Y-29) in Belgium and then later to Kirzengren airfield in Germany on April 30, a week before VE day . Hess became the group’s operations officer and was promoted to Major. He flew a total of 63 combat missions in P-47s during the war.

After the war in the fall of 1947, Hess attended Ohio State University in Columbus to study for his doctorate in History. Just before he was about to get his doctorate, he was recalled back to active service in the USAF on 5 July 1948. He was ordered to Mitchell Air Base in New York where he was assigned to the officer-procurement program. His assignment was traveling around the country, visiting colleges and universities to meet with college presidents and executives, and examined young men for admission to and training in the Air Forces. Hess did good job in the procurement program and eventually took over the office of this liaison activity. In April of 1950, Hess’s name came up for rotation overseas. The assignment was with the US occupation forces in Japan and he accepted it.

In Japan, Hess was assigned to the Yokota Air Force Base as an information and education officer. During his two week tours as duty officer in the radar filter center, where 24 hour surveillance was maintained over all air activities, he tracked the flights of Communist aircraft on the radar screen. Some would frequently approach the 38th Parallel which was an ominous threat. The appearance of these aircraft was the signal to alert our intercept planes. As soon as our planes got up and appeared on the Communist radar screens, the Communist planes retreated to the north. While off-duty, he supervised education programs for Air force personnel and their dependents. He was also busy setting up schools at the Yokota, Johnson, and Tachikawa bases in Japan and assigned civilian teachers from the US.

Then on June 25, Hess heard the news that the North Koreans had crossed the 38th Parallel in force. A couple days later a North Korean Yak fighter fired on a loaded USAF C-54 transport near Suwon. A USAF F-82 Twin Mustang all weather fighter promptly shot it down and the air war had began. Hess immediately requested for hazardous duty but nothing happened. He bombarded his commanding officer with written requests, telephone calls and personal pleas. The last he heard that he was going to be assigned as a liaison officer and courier between Tokyo and Seoul – no hope for combat.

His luck then had changed. He happened to overhear the wing executive officer speaking to someone in command HQ looking for a major who would volunteer for a special assignment in Korea. Hess immediately went to the wing exec and told him that he wanted the assignment no matter what it was. The wing exec told that they had to go to the commanding officer who would make the selection. Another major who also applied for the assignment was waiting when they arrived. After the commanding officer had interviewed Hess and the other major, he decided to determine which of them would get the assignment by a lottery. He told them to pick a number between 0 and 9; he then would flip through the pages of a book. Whichever one of them had the number closest to the last digit of the page number which he stopped on would win. Hess picked 7 and held his breath as he watch the riffling pages of the book. Hess’s number 7 came up. He was so elated that the other major left with a laugh.

Film: “By Faith I Fly”, the Dean Hess story

Bout One

On 26 June 1950, the US agreed to provide 10 North American F-51D Mustang fighters to the ROK Air Force. These F-51Ds had been unarmed target tugs in Japan for several years and they were in a sorry state of maintenance. With missing instruments, non-functioning or no radios, they were hastily made combat ready. The US Far East Air Force formed the Bout One Project, an improvised training unit commanded by Major Dean Hess, which consisted of 10 pilots, 4 ground officers and 100 enlisted men from the US Air Force. Their objective was to train a group of South Korean pilots to fly the US fighters.

Ten ROK pilots, led by Colonel Lee Gun Suk, flew to Itazuke Air Base in Japan, received about half an hour of orientation, and on 2 July 1950 flew the Mustangs to Taegu Airfield in Korea (today Daegu International Airport). After arrival at Taegu, the unit was re-designated as the ROKAF 51st Provisional Fighter Squadron, but remained under US Air Force command, as the South Koreans were not deemed prepared to operate their new aircraft effectively. After the South Korean pilots were properly trained and checked out, they would become the instructors for future ROKAF pilots.

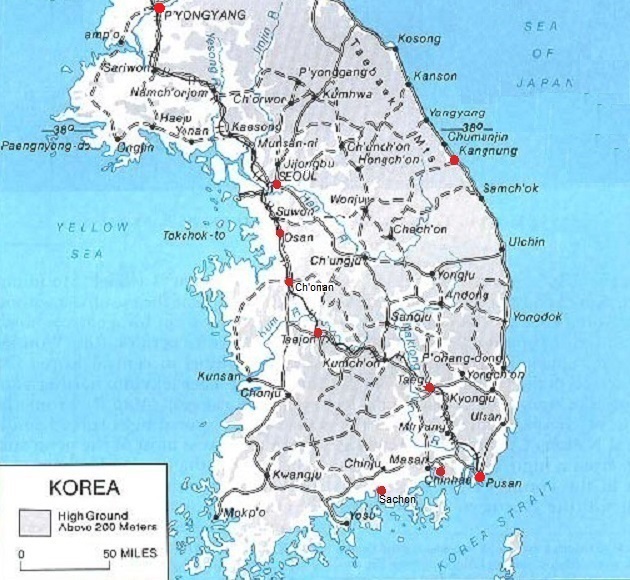

Map of Korea

Taegu

The airfield at Taegu (K-2) was located northwest of Pusan. Bordered by a rice paddy, it had no foundation. The runway was vague path in a bog with no rock ballast or hard surface upon which to operate aircraft from. The rest of the establishment consisted of a couple of ramshackle buildings. A large amount of work had to be done before the field could receive the F-51Ds.

For ground defense, there were six M45 Quad mounts, each mounting four .50 Caliber M2 MGs. These would have been sufficient except that only one MG out of the total 24 was able to fire. Having been informed that they were under surveillance by guerrillas and spies in the surrounding hills, and having seen their signal lights at night, they improvised a maneuver to conceal their weak field defenses. They took the battery with the one working MG to one side of the field and test fired the MG from that position. Then they dismounted the working gun from its carriage, put it in a Jeep, and carried it over to another battery where they then mounted it on that battery and test fired it again. They repeated this procedure for each of the batteries hoping to give the enemy the impression that the field was well defended. Eventually, all the MGs were made fully operational.

A small mobile radar unit mounted on a trailer had came from one of the islands in the South Pacific where it had been since WWII. Since half its parts were missing, it was not able to receive or send. Only the antenna rotation functioned. They set it up with a tent on a hill top overlooking the field. Guerrillas hidden around the field saw well-armed airmen going up the hill for a shift and others came down, while day and night the little antenna rotated as though it was scanning for enemy aircraft. What the guerrillas did not know was that the “operators” were going up to the tent on the hill only to sleep. Later, they finally received the needed replacement parts from Japan and were able make the set operational.

Into Combat

Although the 51st Provisional Fighter Squadron was supposed to be a training unit, the situation on the ground required the unit to be committed to combat a couple of days after their arrival at Teagu. Since the South Korean pilots were not ready, they flew joint training/ground attack missions with their USAF instructors, sort of like on the job training under fire. There was a language barrier between the South Korean pilots and the USAF instructors. The Americans did not speak any Korean and only a few Koreans spoke some English.

The oriental markings on the ROKAF F-51Ds made considerable confusion among the unwary or the trigger-happy, and at times they were fired upon by UN ground units. They were not able to take evasive action as it was considered a hostile action. The only hope was if the ground fire missed on their first pass, they would recognize their F-51Ds on a second glance and realize that they were friendly. The reverse of the situation was a good thing. Later the misunderstanding of their planes’ oriental markings by Chinese troops allowed them to close in enough to fire upon them without receiving return fire from the Chinese.

The South Koreans flew F-51Ds without bombs mounted since there was the risk of them crash landing on takeoff and the bombs were too expensive. The 5 inch (127 mm) High Velocity Aircraft Rockets (HVAR) were stocks left over from WWII and due to their age they were very erratic, although they did proved to be good “tank stoppers” when they impacted the treads of Soviet built T-34/85 tanks.

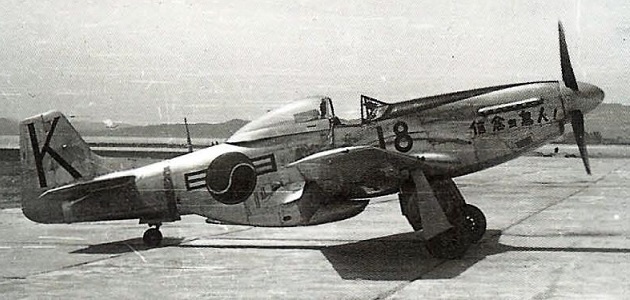

This ROKAF F-51D was flown by one of the USAF instructors. The ROKAF insignia was only in one position on the wings and on the opposite side compared to USAF planes.

A USAF instructor pilot returning from a mission in a ROKAF F-51D. Note the USAF stars-and-bars was hastily over painted with the ROKAF insignia.

ROKAF F-51D Number 13 on the airfield at Taegu. In the USA, 13 is considered unlucky by many but in Korea the unlucky number is 4. Four has been deemed unlucky in Korea because it sounds like the Chinese word for “death.” It is also considered unlucky in China and Japan as well.

Osan

The first US troops to be deployed to Korea was Task Force Smith consisting of an infantry battalion of the US 24th Infantry Division supported by six 105mm howitzers. The battalion was both poorly equipped and under strength where it had only two companies of infantry (B and C companies), instead of the normal three for a US Army battalion. C-54 Skymaster transports airlifted the task force into South Korea and by July 1 it had fully arrived and briefly established a HQ in Taejon. Soon afterwards, the task force began moving north by rail and truck to the front lines. On July 4, the task force was dug in on two hills straddling the road north of the village of Osan, 6 miles (9.7 km) south of Suwon and waited for the advancing North Korean forces. At around 0730 hours on July 5, the task force engaged a column of eight North Korean T-34/85 tanks which was supporting the North Korean 4th Infantry Division. The 105mm howitzers were ineffective against the enemy tanks. The first two T-34s were damaged and one was set on fire while the remaining T-34s kept moving forward with the North Korean infantry following behind. The task force managed to hold its lines for three hours, but at 1430 hours, was ordered to withdraw south. The North Korean division continued advancing south towards Taejon.

The ROKAF pilots had a lot of courage and determination, but their feeling that they could handle anything that flew received a setback when one of their best pilots. Colonel Lee made an attack on a North Korean T-34 south of Osan on July 6, only four days after their arrival. During WWII, Lee had shot down over 20 US planes while flying with the Japanese. He was extremely confident of his abilities as a pilot and did not believe that he could learn anything new from the Americans. That was his fatal mistake. The WWII Japanese Zero’s maneuverability permitted it to make a letter S and flip over onto its back during a dive for a quick pullout at altitudes as low as 1400 feet (427 m). However, the heavier and slower F-51D needed to be at least at 2000 feet (610 m) to safely execute the same maneuver. Colonel Lee tried this maneuver in his F-51D and was killed when he crashed into the ground. This was a needless loss of both a plane and an experienced pilot.

Enemy Column

On the morning of Sunday July 9, the squadron was grounded due to bad weather. An enlisted man was trying to get the radio in one of the F-51Ds to work when he received an urgent call for air support from a radio Jeep of the US 24th Infantry Division near the front lines. Since it was impossible for aircraft in Japan to take off and fly through the bad weather, Hess realized that they were the only aircraft available. Their runway was soaked by heavy rain, half of it was covered with 6 inches (152.4 mm) of water. While Hess felt that he should try at least to answer the call, did not think it was right to order any of his pilots to try to take off with him. He asked for volunteers, and Lieutenant Timberlake, one of the original ten instructor pilots, offered to go with him. They taxied out onto the runway through the water and mud, opened the throttle, and barely made it off the ground with their loads of bombs, rockets and .50 caliber ammunition.

During the flight to the front lines, Hess contacted the radio Jeep again. The target was a column from the North Korean 4th Infantry Division moving south on a segment of road south of Ch’onan and north of Taejon. The US ground forces had no anti-tank guns or heavy ordnance capable of stopping the column and they were retreating south. The weather cleared as Hess and Timberlake approached the target area and they could see the enemy column. Tanks, trucks, vehicles of all kinds wound like a disjointed snake somewhere from 10 to 15 miles (16 to 24 km) along the road. The situation required more than their two aircraft. Since Hess had the only working radio, he hand signaled to Timberlake what he wanted him to do which was to bomb the end of the column while he hit the front of the column. They were lucky as their bombs found their targets. The enemy column was neatly buttoned up by bomb craters and knocked out vehicles at both ends of the long column and it could not go anywhere. Hess then sent a ”May Day” message (a general signal for help). He repeated his May Day at intervals for 30 to 40 minutes while they waited for a response. They circled the column, keeping out of range of its anti-aircraft fire. They only attacked vehicles which tried to pass those blocking them or were trying to get off the narrow road. As soon as a vehicle tried to move, they strafed it, leaving the stationary vehicles alone to conserve ammunition.

Then Hess’s May Day finally raised a flyer over Japan who was landing at the Itazuke base in anticipation of the weather approaching Japan. When he answered, Hess described the situation and requested for all available aircraft. Hess also called the radio Jeep and told the observer to contact Taegu to get all of their aircraft up as soon as possible. Within another half hour, the ROKAF F-51Ds arrived over the enemy column. Hess instructed them to circle the enemy and do exactly as what they had done until more help arrived. Hess and Timberlake returned back to Taegu to refuel and rearm while South Koreans continued the holding tactics until US planes began to arrive from Japan. Everything flyable arrived including F-82s, F-80s and B-26s which brought the final punch and the destruction of the enemy column. Hess flew three separate sorties attacking the enemy column that day. Back at Teagu, Hess told his pilots that the Korean war was almost over but how wrong he was. At that time, he did not know that the enemy column was only the spearhead of the invasion force with other North Korean divisions advancing south across the whole Korean peninsula.

Fight for Existence

Circumstances beyond Hess’s control began slowly to push the ROKAF to a premature demise. As the activities around the Taegu airfield continued to build up, more personnel and vehicles were needed to take care of unloading supplies, handling transient aircraft, and keeping the ROKAF F-51Ds flying. In late July, Colonel Curtis lowe arrived at Taegu airfield to take over the increasing airbase responsibilities so that Hess could concentrate solely on training the South Korean pilots. Outranking Hess, Curtis took over command of the whole operation. Distressed by the amount of work and the few men to do it, he soon began to receive more men under his command. Curtis asked Hess to turn over all his vehicles (including his Jeep) and supplies to him, letting him take care of all the airfield maintenance.

Then pilots of the 12th Fighter-Bomber Squadron from Clark Air Base in the Philippines arrived at the airfield to operate from Taegu. The pilots, also known as the “Dallas” squadron, were transported by the aircraft carrier USS Boxer (CV-21) which ferried over 145 F-51D/Ks that were taken from Air National Guard (ANG) units all over the United States. It would been days before their planes could be unloaded and made combat ready. Since the ROKAF planes were combat ready, they were given to the Dallas squadron. That was a severe blow to the South Korean’s morale since they were almost at the point of becoming proficient enough to fly effective combat missions.

Hess was also worried about the ROKAF insignia on the F-51Ds which the USAF squadron were then flying. He kept trying to persuade them to put on the correct USAF insignia on the planes, but to no avail. Hess was told they were only going to use the ROKAF planes for a few days but sure enough an incident occurred where the South Korean pilots, sitting in their tents, was blamed. The Dallas squadron pilots went out to strafe some front line positions. Instead, due to a wrong direction from a ground controller, they strafed US troops. Hess was called to the advanced HQ of the US 5th Air Force in Taegu and was asked why the South Korean pilots were not better instructed. Furiously, Hess answered that they were USAF pilots flying planes with ROKAF markings. It was an understandable mistake, as US troops were scattered all over and pressure was heavy for close air support. But to have Hess’s outfit blamed for another unit’s error just added to the frustration.

Another blow came to the South Koreans, Colonel Lowe was instructed to form the 6002nd Fighter-Bomber Wing (FBW) and to absorb all US personnel at Taegu. Hess received word that the Bout One project had been dissolved and the his unit was part of the 6002nd FBW with Colonel Lowe in command. Lowe wanted Hess to be part of this staff as operations officer. Hess was told the ROKAF would no longer exist. All the ROKAF planes were to be transferred to the 6002nd and the Korean pilots sat in their tents waiting for their orders which probably would been transfers to ROK infantry units.

Hess fought to keep the project and the future of the ROKAF alive. He went to see Lieutenant General Kim Chung-yul, Chief of Staff of the South Korean Air Force and then to Brigadier General Edward Julius Timberlake, Deputy Commander of the US 5th Air Force and pleaded his case for the Bout One Project and the future of the ROKAF. Hess did persuade General Timberlake and his request was granted. Hess was allowed to have the remaining 6 operational ROKAF F-51Ds since the Dallas squadron planes had arrived in much better shape than expected and they were going to abandon them anyway. He was also allowed one other US officer and a few enlisted men, and to take the unit somewhere where they would not be interfered with. Hess returned to the airfield with his news that the ROKAF pilots were no longer grounded. He asked for volunteers among his fellow US officers to go with him but none offered as they did not want to spend the rest of the war in a training unit. He was able to muster around 30 US enlisted men to go with him. He was not allowed any equipment because it was all taken by the 6002nd. They had no tents, only one cooking stove and very meager supplies. They would have to scrounge for the rest. They did have 6 F-51Ds and were operational again.

Sachon

Hess received instructions to setup an airfield at Sachon (K-4) which is on the south coast of the Korean peninsula west of Pusan. His primary duty was to maintain the field as an emergency airstrip for the USAF. As a secondary job, he could train pilots for the ROKAF. Hess and his band of gypsies obtained some old trucks which were falling apart on their wheels. The Koreans had the uncanny ability to keep this junk running as they drove down to Sachon. Parts of the hoods were missing, tires were bald, and a number of old batteries were connected in series to supply power.

They arrived at their new airfield on July 27 and all the men moved into some old buildings by the hard surface runway with Americans and Koreans bunking near each other. Hess planned to ferry all 6 of the F-51Ds down himself, one at a time, to this excellent field built by the Japanese. By the time Hess landed the first plane, the men had made themselves comfortable and were cleaning up the strip. But Hess was met on the runway with the terrible news that they would have to evacuate. The enemy had broken through in a major attack to the west of them. The 24th Division, sent down to Sachon for a rest, was ordered to pull back and the field would soon fall. They had to get moving again.

A moment later, a couple of US Army soldiers drove up in a Jeep and saw Hess’s plane on the runway. They asked Hess if he would strafe one of our own trucks and a gun which had to be left behind. During the retreat, the truck had broken down and they were not able to get the gun out. They did not want either to fall into enemy hands. Sadly, Hess took off, located the equipment, and shot it up. That was the only mission which Hess flew from that particular airstrip, the finest their little group ever had, even if it was only for a day, and it was against a beautiful US truck which they would have given their eyeteeth to possess.

His plane had to be flown to a safe field, but he did not want to start a trip that would separate him from his men. Hess stayed on the ground until everything had been loaded up. As the trucks moved out, Hess noticed guerrilla activity in the hills. Hess took off and circled the small convoy to discourage any enemy attack. Below him the trucks were stretched out on the road north to Chinju. The fuel gauge showed that he getting low on fuel. With a last glance down at the column, Hess swung his plane to the northeast towards Taegu.

Missing Unit

For days, Hess felt a hen without her chicks, a mother separated from her children. His affection for the infant ROK Air Force was exactly that of a parent. At that moment, his men were wandering who knows where in the Korean countryside with the enemy approaching. He was just as concerned about the safety of the ROKAF planes at Taegu, particularly the danger of some US commander with an acquisitive eye but they were there waiting when he got there. Mechanics of the 6002nd were working on them to improve their condition. Then two of Hess’s enlisted men, Sergeants Schuitt and Engel, arrived with depressing news. His unit had located the 24th Division but they had to strike on their own because the division was retreating. They also added that the unit was short of food and discouraged from not knowing what was to become of them. Hess realized it was time to get back to get them. He did not like leaving the planes again, but there was nothing else to do but go find his missing unit.

A number of transport aircraft were delivering radio Jeeps to the airfield. Having no authorization for equipment, Hess would not be scheduled to get one. But if he was to join his men, he had to have a Jeep, it was that simple. Hess went to the plane where a Jeep was being unloaded and asked the sergeant in charge if it was for him. The sergeant looked at his form, answering that he was not sure whom it was for; it was merely marked for the 5th Air Force. Hess told him that it must be his, jumped into it, and drove away. He ten went to the motor pool and latched onto a quarter ton trailer. The motor pool officer came out and wanted to know what was going on. Hess told him that he had a job that needed a trailer, but before the officer could object, Hess drove off with it. From there, Hess went around to the mess hall and had the trailer loaded up with C rations. After picking up his sergeants, Hess rapidly left Taegu to begin his quest.

Normally, The drive to the location where Schuitt and Engel had left the others should had taken an afternoon. Driving at night, they were still on the road after fifteen hours. Driving through the mountains, they got lost; they got stuck; and they forded streams. They had trouble with the radiator. luckily, they located an old Korean man who had soldering equipment and for a couple cigarettes he repaired it. On they went looking for the lost South Korean Air Force. Hess was beginning to think that they would never find the unit when suddenly there they were moseying along the road with men and equipment piled high on four forlorn trucks. Their uniforms fatigue uniforms were covered with mud. A couple of them wore driver’s goggles, picked up who knows where.

They were all together again as one unit but the problem was where to go. One of the Koreans remembered a former Japanese naval base was at Chinhae, east of Masan, and it had some old Quonset huts. Since they had no tents, the main objective was to find shelter and Chinhae sounded promising. They turned around and started along the southern coast to the east.

Chinhae

The unit arrived at the Chinhae airfield (K-10) and found the found the abandoned huts as expected, plus a usable administration building. The only problem was that the runway was too short. At one end was a sea wall and at the other was some rice paddies. No matter how many times Hess paced off the runway, it only measured 2750 feet (838 m). According to the technical manuals, the F-51 required to operate from a runway that is 3200 feet (975 m). There was nothing to do but try it. Hess hitchhiked back to Taegu and flew one of the F-51Ds to Chinhae. As he circled above, it looked much shorter. It also narrowed at the end, and the framework of a large steel hanger which the Japanese never finished was on one side of the strip. Due to his excellent piloting skills, Hess did managed to land the F-51 on the short runway. Hess went back to Taegu and brought down another, planning to shuttle back the remaining four as soon as he could. He did not immediately fly them operationally, but only had the Koreans maintain them and get them in better shape for combat. Then Hess tried to find another US pilot so he could start the fighting-training operation again.

Out of the blue another US pilot arrived. Captain Harold Wilson was a public information officer going from base to base with a photographer, finding stories about USAF operations. After hearing our their treks from one field to another, he visited the odd small unit in search of a story. After learning how badly they needed another pilot, he asked if he could lend a hand. Wilson helped Hess ferry down the remaining four planes at Taegu. At first, Wilson was a temporary helping hand and never left the unit. Ultimately, Wilson requested a permanent transfer to the outfit and over the following months flew over 50 combat missions.

The short strip at Chinhae was no place for the South Koreans to practice since they only have a few planes and none could be replaced. About 70 miles (112.7 km) to the east of the Pusan was a long macadam strip used only for cargo aircraft. A couple of the planes were sent there for the Koreans to practice on. A marking line was added at 2750 feet and daily the Koreans practiced landings on the shorter runway length.

Pusan Perimeter

The North Koreans had forced the UN forces back to the “Pusan Perimeter”, a 140 mile (230 km) defensive line around an area on the southeastern tip of South Korea that included the port of Pusan. The boundary was around Masan, north along the Naktong River to Taegu and east to P’ohang-dong on the eastern coast. The UN forces consisting of the ROK, US and UK Armies were on the brink of defeat and rallied to make a last stand which lasted from 4 August to 18 September 1950.

During that time, the UN ground troops were in desperate need of air support since all units were retreating south towards Pusan. The 25th Division based at Masan requested to Hess make air strikes for units that were taking heavy casualties on the ground. The demands for close-support missions grew until Hess was answering a half dozen calls a day using the code sign “MacIntosh One”. Hess became quite familiar with the 25th Division’s operations, and the coordination between the ground and air became excellent. War correspondents described Hess as being a one man air force for the US Army which displeased the unit because they felt they should been identified as being part of the USAF. In military parlance, they became known as “freewheelers”.

Hess was disturbed when he was awarded the Silver Star. General William Benjamin Kean (9 July 1897 to 10 March 1981), the commander of the 25th Division, happened to be in the area and witnessed Hess knocking out an enemy gun position and then expended the rest of his ammo on strafing enemy troops nearby.

Expansion

The short runway at Chinhae finally caught up with them when a US 5th Air force C-47 cargo plane crashed landed while flying in supplies. Although there were no casualties, except for the plane, 5th Air force HQ forbade all its aircraft to land at Chinhae which cut them off from their most valuable source of supplies and forced them to depend on ship and truck transport. But they grew shorter on supplies, even lacking replacement parts for their planes.

The training program clearly demanded additional personnel. After requesting it, Lieutenant Ernest Craigwell was transferred from a unit in Japan, an ex-crew chief and a self-educated African American with a fine knowledge of mechanics. As a pilot and a junior officer in the unit, Hess made him the aircraft maintenance officer. Wilson, Craigwell, and Hess worked out a complicated shuttle system so that the Koreans could fly combat missions. Two Koreans would fly out with one of them accompanying them. They would fly over enemy lines, perform their mission, and the Americans would land at Chinhae while the Koreans landed at the longer practice strip at Pusan. Then two of them would fly a AT-6 Texan over to Pusan and fly back the two F-51s back to Chinhae. The Koreans would then fly the smaller AT-6 back to Chinhae.

Due to the lack of supplies and the time it took shuffling planes between Chinhae and Pusan, the runway at Chinhae had to be lengthen. General Kim Chung-yul got a civilian contractor to do the job. The operation required a large number of Korean workers, oxcarts and baskets in which dirt was carried from a small hill on the edge of the airfield to the runway and out to the rice paddies. General Kean provided a road company of US engineers who contributed a road scraper, shovels, and dynamite to blast rock for ballast. But mostly the stones were carried by hand by 300 patient and tireless Koreans. Slowly the strip was lengthened from 2780 feet to 3500 feet.

Training

In early August 1950, the ROKAF officially designated the unit as the 6146th Air Base Unit with the code name “MacIntosh”. The unit grew larger in size and then their numbers leveled off. They still had only three USAF pilots, Wilson, Craigwell, and Hess. Eight of the original ten Korean pilots still flying were checked out in the F-51. On the ground, there were 30 USAF airmen, about 100 ROK airmen and 75 ROK air cadets which General Kim Chung-yul had recently sent for basic training on the field.

Training the ROK pilots in combat was probably the units most original contribution to art of aerial warfare. Their procedure from the start was a version of the “buddy system” where Koreans were under the tutelage of two Americans. Most of the ROK pilots learned enough basic English to grasp what was being explained to them.

The Korean who most often flew with Hess at Chinhae was a Lieutenant who, it was said, had came down from North Korea in 1948. He was accepted into the ROKAF only after convincing them of his dedication to the democratic cause. He had seen with his own eyes what happened where Communism reigned. While both General Kim Chung-yul and Hess believed him to be completely sincere and trustworthy, some Americans did not agree. They suspected that he might be a Communist saboteur and they advised Hess not to fly with him. That irritated Hess for he liked the man personally and knew about his excellent service record since coming south. Hess took him as his flying partner in the buddy system and later he justified Hess’s faith in him magnificently.

Hess, in the center, is giving ROK pilots instructions in the hanger at Chinhae. Note the numbers 8 and 10 on the two pilot’s flight vasts to the left. They are probably their plane numbers. On the right could be Hess’s Korean Lieutenant flying partner.

ROKAF F-51D number 6 was was one of the original ten Mustangs to the Bout One Project. It sustained so much damage that it could no longer repaired for combat missions so it was relegated for training flights only. It is seen in the hanger at Chinhae in August 1950.

ROKAF F-51D number 2 was also one of the original ten Mustangs. Here it is seen on the Chinhae airfield in August 1950.

This is a close up of the tail of F-51D number 2. Note the disjointed letter “K” painted on the tail and the red trimming around the edges of the tail.

Due to an earlier loss, the number of the unit’s F-51Ds were reduced to five. Hess had been working on the assumption that the ROKAF would keep going only as long as their aircraft lasted. Then, out of the blue, came an order from General Timberlake that they would be maintained at a level of 10 planes. It was the first indication that the ROKAF would not end when the last handful of battered F-51s had been lost. It was the first evidence of strong official backing and approval of the ROKAF.

Identity Crisis

Some of the younger US pilots were dangerous to fly in the same sky with. One morning, Hess was flying out of Chinhae over the US 25th Infantry Division sector along the Naktong River searching for targets of opportunity when four USAF fighters bore in on him. The obviously new pilots had never seen the markings of ROKAF planes and decided he must be the enemy. Two of the pilots got on Hess’s wings while the other two stayed behind him. One kept firing at Hess’s wing tip. They were trying to box Hess in, force him down, and capture his plane. Hess made several radio calls trying to identify himself as friendly, although he could hear them talking back and forth, but he could not get through to them. Hess then radioed the ground controller to advise them who he was. The ground controller replied that there were four USAF aircraft working outside their regular sector and that he could not make contact with them.

The planes circled for 20 or 30 minutes. When two of the planes were on Hess’s wing, Hess would adjust his throttle slightly and maneuvered so that he would overlap one of them. That way they would have hit their wing man if they opened fire on him. In desperation, Hess took off his helmet, but he was so tan from flying in the sun that they could not distinguish him from the darker Koreans. Then finally, Hess looked down at the pilot that he was hugging just as he glanced apprehensively over his shoulder at him, Hess thumbed his nose at him, hoping the strictly American hand gesture would identify him as friendly. Shortly afterwards, the four planes broke off the engagement and returned to base, either because they were uncertain about Hess’s identity or they were low on fuel.

Seoul

The ROKAF F-51Ds could only be truly effective based near the front lines. So when the UN ground force advanced, they had to pack up and advance too. On 15 September 1950, UN forces successfully landed at the port of Inchon and began fighting inland towards Seoul. Kimpo Air Base was taken on September 18. General Kim Chung-yul and Hess began working on a plan to transfer the unit back to the national capital, nearer to the new front lines. Hess went to General Timberlake to get his permission, and he authorized moving the unit to Kimpo Air base which was once the international airport near Seoul. Although the unit was not fully equipped, they did picked up a few additional Jeeps, a couple of trucks, and some carbines (rifles). They also laid their hands on a gasoline truck which held 5000 gallons (18927 Liters).

General Kim Chung-yul and Hess flew up to Kimpo Air base a few days after it was taken. The US Marine divisional head with whom Hess was to coordinate with was cooperative, but the USAF Colonel at Kimpo had a indifferent attitude toward General Kim Chung-yul, refusing to recognize his rank. He was going to assign them to an area of the base called “Mud Haven”, appropriately named, where they could not have taxied their planes in wet weather and the men would have been sleeping in mud puddles. After a heated discussion, they declined colonel’s offer.

This damaged North Korean Yakovlev Yak-9P was captured by the US Marines at Kimpo Air Base. It must had bad luck since the tail number contained a 4.

This North Korean Ilyushin Il-10 “Beast” ground attack aircraft was also at Kimpo. The tail number 44 must made it really unlucky to be captured intact. This plane was shipped back to the USA for evaluation.

There was only one option left, to make their own base. The area map showed an abandoned airfield near Seoul at Yongdungpo, a village on the south side of the Han River. There, beside some burnt and flatten buildings, they found a sizeable airstrip which was overgrown with weeds and heavy brush. Hess flew back to inform General Timberlake of their discovery and their plans. The general thought that Hess was out of his mind to take on such a job. But he did sign the authorization to move the unit on 26 September 1950. However, he could not provide Hess any logistic support.

Without wasting any time, they procured an LST (Landing Ship, Tank) from the Korean Navy to transport the unit from Chinhae to Inchon. The sea voyage took two and a half days. From there they would travel overland to Yongdungpo. Not wishing to leave their F-51s unguarded at Chinhae, Hess assigned a US pilot, one of two who had recently joined the unit at Chinhae, to ferry them to taegu. He was ordered to stand by until the new field was setup at Yongdungpo and ready to receive aircraft. Several Korean pilots were with him, similarly instructed not to fly missions but to wait until the new field was ready. Instead, once at Taegu and against orders, they began to fly combat missions without crew chiefs or armorers to care for the planes.

The unit reached Yongdungpo in late September 1950 and the field looked worse than when Hess last seen it. They did not have a single piece of equipment suitable for runway construction. Members of other units would stop by, ask what was their business, and then laugh aloud at the idea of building an airstrip there. They had no other option but to call on some civilian help. Almost a thousand of Koreans including old men, women and children appeared on the field with whatever hand tools they could bring. Again, all the hard work was done by hand. Within a week, the airstrip was ready to receive planes.

About ten days later, General Timberlake’s plane landed at the Seoul Air Base (K-16) at Yongdungpo. The general personally promoted Dean Hess to Lieutenant Colonel.

The unit was ready to fly and fight again. Their unit identity had crystallized and the field’s location was a special advantage being so close to the main source of supplies. They were able to obtain all the fuel, bombs, rockets and .50 Caliber ammunition that they needed. They were also informed that their complement of F-51s would be raised from 10 planes to 20 and maintained at that level.

This F-51D was assigned to the unit on 8 October 1950 and it became Hess’s personal aircraft, number 18. Before being transferred to Korea, this plane had served with the 182nd Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, Texas Air National Guard. The writing below the canopy was “Last Chance.”

On the engine cowling of Hess’ F-51D was engraved with a translation of his personal motto. First Sergeant Choi Won-moon, a ROKAF mechanic who was the plane captain, translated “By Faith, I Fly” into Korean.

Pyongyang East

At Seoul, the old problem of encroachment began to plague them, being the closest airfield to the front lines. One outfit after another began to move in, used their field, dipped into their supplies, and monopolized all the facilities. From the beginning, other units had been dropping in usually in need of something. Practically everyone outranked them and their supplies were dwindling even before K-16 became operational. General Timberlake assured Hess that since the base was his idea and creation, no other unit would interfere with their operation in any way. Then a troop carrier command flew in 30 Curtiss C-46 Commando transports with supplies and troops bound for the front lines. The congestion just increased. The established operational outfits were taking precedence over what was still essentially a training program. They were moving in less and less space, while their airborne activities were curtailed by the swelling traffic on the runways. The same situation with the same solution, they had to move again.

Scouting around to the north, Hess located an airstrip about 8 miles (12.9 km) east of Pyongyang, the former Communist capital which UN forces had taken on October 20. Built by the Japanese and long abandoned, it was declared unusable. Hess flew over the field to take a look. A battle was fought over it, a UN airborne unit landed on the field and the enemy lines collapsed. Hess blessed the boys dangling in their parachutes as they gave him an airfield.

With his claim staked, Hess travelled the well known road back to General Timberlake. He told the general about the new site and described it. Timberlake thought Hess was surely off his trolley, for according to his information there was no field there at all. When Hess told him that he had been there and it was an excellent field, Timberlake not only told him not only to proceed but offered to provide an airlift.

The new field became Pyongyang East K-24 on 28 October 1950 and it proved to be an ideal location for combat operations. Natives in the area welcomed them gladly and again large numbers of them came to the field and offered to work for no reimbursement of any kind since they were free again.

It is not clear if Hess’s original F-51D was written off and this is a replacement plane or the original F-51D was just repainted. Note the different style of the number 8.

F-51D number 18 with new paint scheme. A red panel was added above the exhaust stacks and the Korean “By Faith, I Fly” was painted over white instead of natural metal.

Hess’s F-51D number 18 is in the background. Note the sandbag and fuel drum revetments around the parking spots to the right. The USAF fuel truck in the foreground probably is the one they acquired in Seoul.

This is my close up of F-51D number 18 in the photo above. The ROKAF insignia on the fuselage appears to be not standard. On both sides of the taegeuk, there are only two black or blue bars, maybe with white between them, but no red bar in the center. Note the red panel above the engine exhaust stacks has faded off probably due to the exhaust heat.

Taejon

On 19 October 1950, tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers of the People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) began crossing the Yalu River, the border between China and North Korea, at night to avoid detection by UN reconnaissance aircraft. On October 25, the first shots fired between the PVA and UN forces were at Onjong, about 85 km (53 miles) south of the Yalu River. The advancing PVA forces forced the UN forces in North Korea to retreat to the south. As UN units were moving pass Pyongyang southward, the ROKAF pilots provided air cover as long as they could. The ROKAF 6146th Air Base Unit was ordered to abandon Pyongyang East and relocate south to Taejon Air Base K-5.

On December 6, the unit reached Taejon Air Base K-5. The field was short, narrow and terribly muddy. It had no parking area, and had never been planned for use as a fighter strip. Stii, these conditions which made no one else want it were why they were assigned it. It was their own, and it posed another challenge which can be overcome like they have done time after time before. As soon as the trucks begin to arrive overland from Pyongyang, they started to make it operational. The weather was bad, it either rained or snowed throughout much of the day. They tore down some old Quonset huts to rehabilitate others to live in and to build a mess hall. Their precious gasoline stoves soon made them relatively comfortable.

Flying proved to be almost impossible. The runway conditions made operations especially difficult for the ROKAF pilots who were not checked out in the F-51s and they did not want to risk the more experienced ROKAF pilots. So a unit detachment of the more experienced ROKAF pilots was sent to Cheju-do (an island off the southern coast of Korea) to conduct an intensive training program for Korean personnel while the few US pilots used Taejon airfield to fly combat mission when possible.

Operation Kiddy Car

Many helpless Korean children were orphaned by the war and US 5th Air Force Airmen in Seoul decided to unofficially feed and shelter them. Chaplain Lieutenant Colonel Russell L. Blaisdell, Dean Hess and others organized relief for the children. Blaisdell, Hess, and with the help of Staff Sergeant Merle “Mike” Strang and South Korean social workers saved many orphans from near certain death by collecting them from the streets. Blaisdell worked to find shelter and medical care for children, while he and Hess arranged food, money and clothing contributions.

When the communist Chinese forces were pushing the UN forces south, they threatened to take Seoul, the capital of South Korea. The Korean civilian population faced a dire crisis and were retreating south. Blaisdell tried several avenues to save nearly 1000 children by ground or sea convoy, but nothing was available. Blaisdell and Hess devised a plan to transport the children to Cheju-do. This plan became known as Operation Kiddy Car. As the Chinese forces approached, Blaisdell’s persistence had paid off, 5th Air Force Chief of Operations Colonel T.C. Rogers located 16 Douglas C-54 Skymaster transports to evacuate the orphans. Commandeering several trucks at the port of Inchon, Blaisdell had the orphans and rescue workers transported to nearby Kimpo airfield and the waiting aircraft.

A young Korean orphan boy walks up the loading ramp of a C-54 at Kimpo Airfield. The airmen walking down the ramp towers over him. Others in the background are being helped out of the trucks.

The transports flew the orphans to Cheju-do, where Hess made arrangements to receive them. With contributions from US troops and many others, an orphanage established there by Hess was able to accept even more children.

1951-53

On 22 March 1951, the unit was relocated back to Seoul Air Base K-16. In May 1951, Major Harold H. Wilson took command of the ROKAF 6146th Air Base Unit.

On 18 June 1951, training in the operation and maintenance of L-4, L-5, L-16, T-6, and F-51 aircraft for ROKAF personnel was setup at Sachon K-4. On 15 January 1953, the group moved to Taegu K-2 and it left a detachment at Sachon to continue that training. Once trained at Sachon, the ROKAF pilots deployed to Kangnung K-18 near the 38th parallel, where another of the group’s detachments had been based since the end of 1951. From Kangnung, the ROKAF F-51s provided air support to UN infantry divisions positioned along the Main Line of Resistance (MLR) in eastern Korea.

Originally organized as the ROKAF 6146th Air Base Unit in August 1950, the organization elevated to group-level (wing) in August 1952 then was re-designated to ROKAF 6146th Air Advisory Group at that time, and finally re-designated to ROKAF 6146th Air Force Advisory Group in July 1953.

ROKAF air cadets are being trained to mount bombs on a F-51D at Sachon Air Base K-4 in 1952. The WWII GMC F-3 Fuel Service Truck in the background has “KAF WING K-4” painted on the front bumper. The instructor appears to be sitting on the wing of the Mustang on the right.

A flight of ROKAF F-51s flying over mountainous Korean countryside. A superstitious ROKAF pilot probably would say that F-51D number 34 is unlucky to fly.

ROKAF F-51s on the flight line. Note the higher plane numbers.

This flight of ROKAF F-51s either just took off or are coming in for a landing as all the planes have their tail wheel down. Number 200 in the center is a TF-51D which was a two-seat, dual-control Mustang trainer. They were flown with some combat missions carrying a non-pilot observer.

Armistice

When the armistice was sign on 27 July 1953, the ROKAF, headquartered at Taegu, consisted of 118 aircraft and 11500 personnel. The 118 aircraft comprised of 78 F-51s, 1 C-47, 17 T-6As, 6 L-16s, 6 L-5s, and 10 L-4s. F-51 pilots of the ROKAF flew about 8500 combat missions during the war. Of the 115 ROK pilots who flew F-51 combat missions during the war, 39 flew 100 or more missions and 17 were KIA.

During the war, the ROKAF planes were identified by a number only. After the hostilities ended, the letter “K” was added to the number on the fuselage.

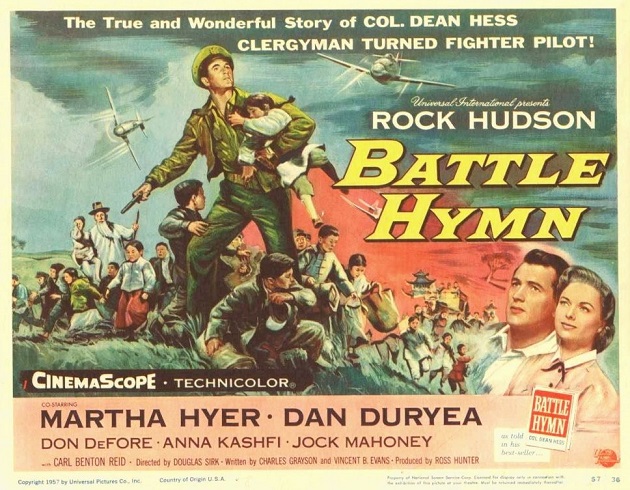

Book/Movie

Dean Hess first published his autobiography “Battle Hymn” in 1956. In 1957, the movie “Battle Hymn” was released by Universal Studios based on the book. It was directed by Douglas Sirk and starred actor Rock Hudson as Lieutenant Colonel Dean Hess. Dean Hess used the royalties from his book and the movie to fund a new orphanage in Seoul.

The real Lieutenant Colonel Hess was a technical advisor to Universal. The studio’s first choice to play the lead was Robert Mitchum but Hess had a hand in vetoing him because he had reservations about the actor’s character. Unable to film in Korea, locations were filmed at Nogales, Arizona (near the Mexican border) which provided at least similar landscape. On Soon Whang, Director of the Orphans Home of Korea brought to the US 25 orphans who were airlifted during Operation Kiddy Car and they appear in the film, older of course.

For the film, 12 F-51D Mustangs of the 182nd Fighter Squadron, 149th Fighter Group, Texas Air National Guard were enlisted by the USAF to provide authentic aircraft of the period. An additional surplus F-51 was acquired from USAF stocks to be used in an accident scene where it was deliberately destroyed. For the air lift scene in the film, five Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar transports were used instead of the sixteen C-54 Skymaster transports which were used in the actual event.

In the film, there was an incident where a pilot named Lieutenant Maples (played by James Edwards and based on Ernest Craigwell) accidentally strafes a truckload of civilian refugees that happened to be near a convoy of North Korean troop trucks. In the actual incident, it was a fishing junk full of civilian refugees that happened to be near an amphibious assault by North Korean landing craft. The film also did not include Hess’ involvement in a similar accident, in which he inadvertently strafed a group of refugees due to misinformation received from a liaison pilot.

Film: Battle Hymn (1957) – Rock Hudson, Anna Kashfi, Dan Duryea

Trivial:

In the 1959 pilot episode of the US TV program “The Twilight Zone, “Where Is Everybody?”, a Savoy movie theater sign in a background scene displays “Battle Hymn”.

Today

A preserved example at the Seoul War Memorial is ROKAF number 205, formerly USAF F-51D-25-NA, s/n 44-73494. The camouflaged transport aircraft behind it is a Fairchild C-123 Provider.

The gold Navy flight helmet which Hess wore in Korea, and Rock Hudson wore in the film, is on display at the National Museum of the US Air Force as part of the Korean War exhibit.

MODEL KITS AND DECALS

1/32:

Tamiya 60328 North American F-51D Mustang Korean War – 2020

1/48:

Bronco FB4012 North American F-51D Mustang Korean War – 2020

Scale Bureau 48002 Fighter Yak-9P – 201?

DP Casper Decalset 48015 North Korean Air Force – 1950 – 1953

1/72:

Academy 2205 F-51D Mustang with Ground Vehicle “Korean War” – 2020

Amodel 7286 Yak-9P – 201?

Fly 72038 Ilyushin Il-10 Chinese and Korea service – 2017

Kopro Decalset 73129 Il-10 Beast (Avia B-33) – 2009

A very interesting history. Thanks for posting.

Regards, Chris.

LikeLike

Reading completed

LikeLike