During the Vietnam War from April 1965 to January 1973, the US military claimed about 195 North Vietnamese aircraft were shot down. During the war, the North Vietnamese claimed that only 134 aircraft were lost. It 1972, only five US airmen achieved “Ace” status and three of them were not pilots.

After the Korean War, US fighters (interceptors) were needed to defend against unexpected attacks by Soviet strategic bombers carrying nuclear weapons capable of striking targets in continental North America. Aerial combat was transformed through the increased use of long range air-to-air guided missiles to shoot down enemy bombers. During this period, US pilots received little or no training in Air Combat Maneuvering (ACM) or commonly known as dog fighting.

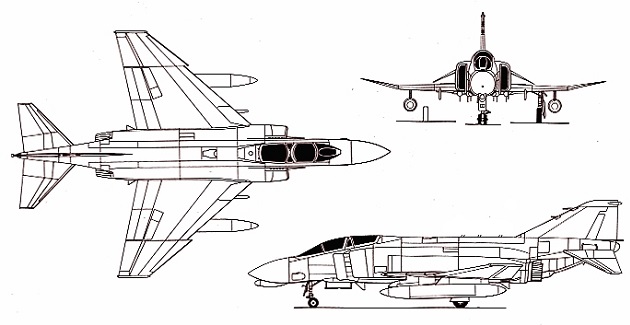

In Vietnam, the main fighter used by the US military was the McDonnell F-4 Phantom II which was a twin-engine, all-weather, long-range supersonic jet interceptor and fighter-bomber. Phantom production ran from 1958 to 1981 with a total of 5195 aircraft built making it the most produced US supersonic military aircraft in history. It was also the first multi-service US fighter used by the US Navy (USN), US Marine Corps (USMC) and the US Air Force (USAF).

“Speed is life” was F-4 pilots’ slogan, as the Phantom’s greatest advantage in air combat was acceleration and thrust, which permitted a skilled pilot to engage and disengage from the fight at will. The Phantom did had some weaknesses. The early engines produced a rather prominent trail of sooty black smoke which pin pointed its position in the sky. Its wide turning radius and lack of an internal gun were disadvantages against the more maneuverable MiG-17 fighter.

US F-4 Variants

USN/USMC

- F-4B: All-weather carrier-based fighter/attack aircraft, 649 built.

- RF-4B: USMC tactical recon version of F-4B, 46 built.

- F-4J: Improved F-4B version for the USN/USMC, 522 built.

USAF

- F-4C: All-weather tactical fighter, ground-attack version, 583 built.

- EF-4C: F-4Cs Wild Weasel ECM aircraft, 36 were converted.

- RF-4C: All-weather tactical reconnaissance version for USAF, 503 built.

- F-4D: F-4C with updated avionics and AN/APQ-109 radar, 825 built.

- F-4E: USAF version with internal M61A1 Vulcan 20mm cannon under the nose with 640 rounds, 1370 built.

Specifications

Length: 63 ft 0 in (19.2 m)

Wingspan: 38 ft 5 in (11.7 m)

Width: 27 ft 7 in (8.4 m) wing folded

Height: 16 ft 5 in (5 m)

Wing area: 530 sq ft (49.2 m2)

Empty weight: 30328 lb (13,757 kg)

Gross weight: 41500 lb (18,824 kg)

Max takeoff weight: 61795 lb (28030 kg)

Maximum landing weight: 36831 lb (16706 kg)

Maximum speed: 1280 kn (1470 mph, 2370 km/h) at 40000 ft (12000 m)

Maximum speed: Mach 2.23

Cruise speed: 510 kn (580 mph, 940 km/h)

Combat range: 370 nmi (420 mi, 680 km)

Ferry range: 1457 nmi (1677 mi, 2,699 km)

Service ceiling: 60000 ft (18000 m)

Rate of climb: 41300 ft/min (210 m/s)

Fuel capacity

1994 US gal (7550 L) internal

3335 US gal (12620 L) with 2x 370 US gal (1,400 L) external tanks on outer wing hard points.

600/610 US gal (2300 L) tank on the center-line station.

Powerplant

2× General Electric J79-GE-17A after-burning turbojet engines

Thrust: 11905 lbf (52.96 kN) each dry, 17845 lbf (79.38 kN) with afterburner

Armament

Up to 18650 lb (8480 kg) of weapons on nine external hard points, including general-purpose bombs, cluster bombs, TV- and laser-guided bombs, rocket pods, air-to-ground missiles, anti-ship missiles, gun pods, and nuclear weapons. Reconnaissance, targeting, electronic countermeasures and baggage pods, and external fuel tanks may also be carried.

Air Intercept Missiles

4× AIM-9 Sidewinders on wing pylons

4× AIM-7 Sparrows in fuselage recesses

Air-to-Ground Missiles

6× AGM-65 Maverick

4× AGM-45 Shrike, AGM-88 HARM, AGM-78 Standard ARM

Guided Bomb Units

4× GBU-15

18× Mk.82, GBU-12

5× Mk.84, GBU-10, GBU-14

18× CBU-87, CBU-89, CBU-58

The F-4 Phantom crew was two. In the USN\USMC, the crew was a Naval Aviator (Pilot) and a Radar Intercept Officer (RIO). In the USAF, it was a pilot and a Weapon Systems Officer (WSO), nicknamed “Wizzo”. In the aft seat, the WSO or RIO, was directly involved in all air operations and weapon systems of the aircraft.

The phantom crews did had their own assigned aircraft with their names painted on the canopy frames but due to the large amount of work to service the Phantom, they do not always fly their assigned aircraft. For missions, the crews were assigned to aircraft that were available. In the navy on carriers, where the aircraft was spotted on the flight deck was also a factor of which aircraft they are assigned for a mission. Sometimes a crew might never fly their assigned aircraft. Due to various reasons, the WSO (or RIO) would fly a mission with other pilots (or naval aviators).

Kill markings were painted on the aircraft that the kill was made in and credit was also given to the aircraft’s crew chief. One aircraft could accumulate kills scored by several different crews. The kill markings usually remain on the aircraft throughout its service life.

Rules of Engagement

During the Rolling Thunder air campaign from 1965-68, the Rules of Engagement (RoE) were directives issued by civilian authority to guide the conduct of all US aerial operations in Southeast Asia. The RoEs allowed President Lyndon Johnson to apply measured amounts of air power to avoid escalation of the war into WWIII.

Airmen had a hard time with RoEs, with aircraft from the US Air Force, US Army, US Marines, and US Navy all being subjected to different set of rules. On one occasion, US planes based in South Vietnam were allowed to conduct a strike, but aircraft based in Thailand were not cleared to join them.

Aircrews flying over Vietnam had to deal with different rules depending on what airspace they were currently in, what their mission was, where they came from and the type of aircraft they were flying. These rules then vary depending on what the potentially hostile aircraft was doing, who it was operated by, what airspace it occupied, and what type of plane it was. Flight crews received daily updates on what targets were eligible for attack and where.

The rules reduced the effectiveness of the F-4 Phantom. Aircrews were not allowed to bomb or strafe enemy air bases. The aerial target had to be first identified before they can fire their long range missiles and they were also not allowed to engage enemy MiGs over China or Russia air space.

Almost a Vietnam Ace

Robin Olds had flown P-38s and P-51s with the 434th FS, 479th FG during WWII. By the end of the war, Olds had completed 107 missions and achieved a total of 12 aerial victories and 11.5 aircraft destroyed on the ground (the US Eighth Air Force did not count ground kills). Olds named all his aircraft “SCAT” to fulfill a promise he made to his West Point roommate, Lawton “Scat” Davis. Davis washed out of pilot training because he was color blind. First Lieutenant Davis was KIA on 16 January 1945 near Beck, Belgium.

Following WWII, Olds flew with the first USAF P-80 jet demonstration team in 1946. Between 20 October 1948 and 25 September 1949, under the USAF/RAF exchange program, Olds was posted to the No. 1 Squadron flying the Gloster Meteor F.4 fighter. He eventually served as commander of the Squadron at RAF Station Tangmere, an unusual posting for a non-commonwealth foreigner in peace time. Then he commanded several other operational units, and then staff jobs followed. Unable to get a combat posting during the Korean War, Olds became more determined to get into combat when the war in Southeast Asia escalated.

On 30 September 1966, Olds took command of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW) “Wolfpack”, based at Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base. A lack of aggressiveness and sense of purpose in the wing had led to the change of command. The previous wing commander had flown only 12 missions during the 10 months the wing had been in combat. Olds set the tone for his command stint by immediately placing himself on the flight schedule as a rookie pilot under officers junior to himself, then challenged them to train him properly because he would soon be leading them. There was suspicion that this WWII retread was just talking a good game, but Olds soon proved himself to be a master of the F-4 and an inspiring combat leader.

Calling on the skill and guile of the leading members of his wing, Olds planned Operation Bolo. The plan was elegantly simple: F-4 Phantoms equipped with radar jamming pods would imitate the call signs, routes, and flight profiles of the vulnerable F-105s in a bid to coax North Vietnamese MiGs into a trap. On 2 January 1967, the ruse worked and the North Vietnamese ground controllers taking the bait directed their MiGs to intercept not bomb laden Thunderchiefs, but F-4 Phantoms configured for air-to-air combat. In the ensuing air battle, the F-4s and their crews claimed seven MiG-21s destroyed, almost half of the 16 then in service without any F-4 losses. Olds himself shot down one of the seven.

| Date (1967) | TFS | WSO | Aircraft | Tail Code | Call Sign | Weapon | Kill |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2 | 555 | 1st Lt. C. Clifton | F-4C 63-7680 | FP | Olds 01 | AIM-9 | MiG-21 |

| May 4 | 555 | 1st Lt. W. D. Lafever | F-4C 63-7668 | FY | Flamingo 01 | AIM-9 | MiG-21 |

| May 20 | 433 | 1st Lt. S. B. Croker | F-4C 64-0829 | FG | Tampa 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-17 |

| May 20 | 433 | 1st Lt. S. B. Croker | F-4C 64-0829 | FG | Tampa 01 | AIM-9 | MiG-17 |

Olds spray painting a victory star on F-4C 63-7668 on 4 May 1967.

Olds beside F-4C 64-0829 “SCAT XXVII” in late May 1967.

On June 5th, Olds nearly had a fifth kill but the unreliable AIM-4 Falcon missile he launched went ballistic after it initially guided toward the tailpipe of the MiG. In mid June, Olds learned that the US Seventh Air Force, at the direction of Secretary of the Air Force Harold Brown, would immediately relieve him of his command and rotate him back to the States as a publicity asset if he became an ace. Sources state that Olds did shot down more than four MiGs, but those uncounted kills either went unclaimed or were awarded to his wing men.

Olds flew his final combat mission over North Vietnam in F-4C 63-7668 on 23 September 1967.

Bombing Halt

By early 1968, the Johnson administration had become convinced that Operation Rolling Thunder and the ground war in South Vietnam were not working. Though eligible for another presidential term, Johnson announced in March 1968 that he would not seek renomination.

The North Vietnamese who had continuously stipulated that they would not conduct negotiations while the US bombing continued, finally agreed to meet with the Americans for preliminary talks in Paris. As a result, President Johnson declared that a complete bombing halt over North Vietnam would go into effect on 1 November 1968, just prior to the US presidential election. North Vietnam was not the target of intense bombing again for three and a half years. In the 1968 election, Richard Milhous Nixon defeated the Democratic incumbent vice president Hubert Humphrey and became the 37th President of the USA.

On 9 May 1972, President Nixon launched Operation Linebacker, the continued unrestricted bombing of North Vietnam. It had four objectives: to isolate North Vietnam from its sources of supply by destroying railroad bridges and rolling stock in and around Hanoi and north-eastwards toward the Chinese frontier; the targeting of primary storage areas and marshaling yards; to destroy storage and transshipment points and to eliminate (or at least damage) the North’s air defense system, including MiGs.

The first US Navy Aces

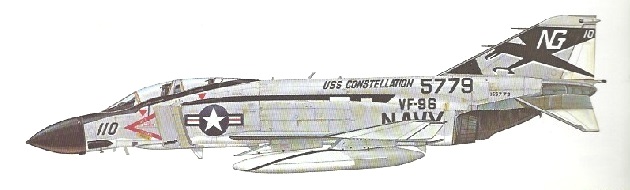

Lieutenant Randy “Duke” Cunningham (Naval Aviator) and Lieutenant Junior Grade (jg) William Patrick “Irish” Driscoll (RIO) of VF-96, CVW-9. USS Constellation (CV-64) Vietnam deployment: 1 October 1971 to 1 July 1972.

| Date (1972) | Aircraft | Tail Code | Call Sign | Weapon | Kill |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 19 | F-4J 157267 | 7267 | Showtime 112 | AIM-9 | MiG-21 |

| May 8 | F-4J 157267 | 7267 | Showtime 112 | AIM-9 | MiG-17 |

| May 10 | F-4J 155800 | 5800 | Showtime 100 | AIM-9 | MiG-17 |

| May 10 | F-4J 155800 | 5800 | Showtime 100 | AIM-9 | MiG-17 |

| May 10 | F-4J 155800 | 5800 | Showtime 100 | AIM-9 | MiG-17 |

On 19 January 1972, Cunningham and Driscoll, flying Showtime 112 north of the DMZ, spotted a pair of MiG-21 Fishbeds. They were directly behind the MiGs and a few miles away, in AIM-7 Sparrow missile range. Due to the Sparrow had proven unreliable, Cunningham ignored Driscoll’s call to fire a Sparrow and switched to the short range heat-seeking AIM-9 Sidewinder. When his headphones growled on acquisition, he called “Fox Two,” and fired the missile. The Fishbed broke off and evaded the Sidewinder, but Cunningham stayed with him and launched a second Sidewinder. It struck the MiG-21 about 1200 yards (1097.28 meters) in front of the Phantom. The explosion blew off the MiG’s tail and the broken fuselage fell to the ground. This was their first victory.

Operation Linebacker aerial bombardment campaign had just began. On 8 May 1972, US Navy planes from the USS Coral Sea mined Haiphong Harbor. Cunningham and Driscoll were flying escort, when a MiG-17 dived out of the clouds, firing at Cunningham’s wing man, Lieutenant Brian Grant. Grant broke away, and the MiG fired a heat seeking ATOLL missile (Vympel K-13, a reversed engineered Soviet copy of the AIM-9B Sidewinder). As Cunningham and Grant twisted and banked and shook the missile, two more MiGs zoomed pass. Cunningham turned on the first MiG and took a long range shot at him with a Sidewinder. The MiG turned hard to elude the missile, but put himself in front of Duke’s Phantom. As the other two MiGs returned and began firing, Cunningham stayed focused on his target. He fired a Sidewinder, which locked on and destroyed the MiG. They did not have much time to cheer their victory because the other two MiGs were on their tail. Cunningham sharply turned to escape, damaging his aircraft in the process, only to look up and see a MiG-17 just above. He could not out turn the MiG-17, but he could out run it. He ducked into a cloud, fired up his afterburner and gave the MiG the slip.

On 10 May 1972, Cunningham and Driscoll flying Showtime 100 were participating in an air strike against the Hai Dong rail yards, on flak suppression, when a score of MiGs challenged them. Cunningham’s Phantom carried two AIM-7E Sparrow long-range missiles (aft positions), four AIM-9J Sidewinder short-range missiles (inboard pylons), and six Mk20 Rockeye cluster bombs. After dropping their bombs on some warehouses, Showtime 100 loitered to cover the A-7 fighter-bombers still engaged. Responding to a call for help from USAF Boeing B-52 Stratofortresses attacking a rail yard in Hải Dương, Cunningham took his Phantom into a group of MiG-17 Frescoes, two of which promptly jumped them. Heeding a “break” warning from Grant in Showtime 113 (157268), Cunningham broke sharply and the lead pursuing MiG-17 overshot him. He instantly reversed his turn, putting the MiG dead ahead. He fired a Sidewinder and the MiG was destroyed.

Cunningham and his wing man Grant climbed to 15000 feet (4572 meters). Looking below, Cunningham saw an enormous melee. A flaming MiG was plunging down, eight more circled defensively, while three Phantoms went after the MiGs within a Lufbery wheel. The Phantoms were at an extreme disadvantage, due to their low energy state. The VF-96 Exec (XO), Commander Dwight Timm flying Showtime 112 had three MiGs on his tail, one being very close, in Timm’s blind spot. Seeing the danger of the XO’s situation, Cunningham called for him to “break,” to clear the Phantom’s hotter J-79 engines from the Sidewinder’s heat seeker, thus permitting him a clear lock on the MiG. But Timm thought the warning was about the other two distant MiGs, and did not heed Cunningham’s first call. After more maneuvering, Cunningham re-engaged the MiG-17 still on his XO’s tail. He called again for him to break, adding, “If you don’t break NOW you are going to die.” The XO finally accelerated and broke hard right. The MiG could not follow Showtime 112’s high speed turn, leaving Cunningham clear to fire. Cunningham fired his second Sidewinder while the MiG was still inside the minimum firing range. But the low speed of the MiG-17 worked against it, as the Sidewinder had time to arm and track to its target. It homed on the tail pipe of the MiG-17 and exploded. Seconds later, Cunningham and Driscoll found themselves alone in the sky. They headed back to the Constellation.

As they approached the coast at 10000 feet (3048 meters), Cunningham spotted another MiG-17 heading straight for them. The MiG’s nose lit up like a Roman candle and cannon shells whiz pass their Phantom. Cunningham immediately pulled up vertically to throw off the MiG’s aim. As he came out of the six-G pull-up, he looked around below for the MiG. MiGs generally avoided climbing contests. They turned horizontally, or just ran away. He looked back over his ejection seat and was shocked. The MiG was barely 100 yards (91.44 meters) away. Both jets roared 8000 feet (2438.4 meters) straight up.

In an effort to out climb the MiG, Cunningham went to afterburners, which put him above the MiG. As he started to pull over the top, the MiG began shooting. Cunningham rolled off to the other side, and the MiG closed in behind. With the MiG at his four o’clock, he nosed down to pick up speed and energy. Cunningham watched until the MiG pilot likewise committed his nose down. As he pulled up into the MiG, rolled over the top, and got behind it. While too close to fire a missile, the move placed Cunningham in an advantageous position. He pulled down, holding top rudder, to press for a shot, and the MiG pulled up into him and shooting. The MiG pilot used the same move Cunningham had just tried, pulling up into him, and forcing an overshoot. The two jets were in a classic rolling scissors. As his nose committed, Cunningham pulled up into his opponent again. When the MiG raised his nose for the next climb, Cunningham lit his afterburners and, at 600 knots airspeed, quickly got 2 miles (3.22 km) away from the MiG, out of the range of the Atoll missile.

Cunningham went back for more and nosed up 60 degrees, the MiG stayed right with him. Just as before, they went into another vertical rolling scissors. Once again, he met the MiG-17 head on, this time with an offset so the MiG could not fire his guns. As he pulled up vertically he could again see his determined adversary a few yards away. Cunningham tried one more thing. He yanked the throttles back to idle and popped the speed brakes, in a desperate attempt to drop behind the MiG. But, in doing so, he had thrown away the Phantom’s advantage, its superior climbing ability.

The MiG shot out in front of Cunningham for the first time, the Phantom’s nose was 60 degrees above the horizon with airspeed down to 150 knots. He had to go to full afterburner to hold his position. The surprised MiG pilot attempted to roll up on his back above him. Using only rudder to avoid stalling the F-4, he rolled to the MiG’s blind side. He tried to reverse his roll, but as his wings banked sharply, he briefly stalled the aircraft and his nose fell through. Behind the MiG, but still too close for a shot.

Now the MiG tried to disengage. He pitched over the top and started straight down. Cunningham pulled hard over, followed, and moved to obtain a firing position. With the distracting heat of the ground, Cunningham was not sure that a Sidewinder would home in on the MiG, but he called “Fox Two,” and squeezed one off. The missile came off the rail and flew right at the MiG. He saw little flashes coming off the MiG, and thought he had missed. As he started to fire his last Sidewinder, there was an abrupt burst of flame. Black smoke erupted from the MiG-17. It did not seem to go out of control, the MiG just kept slanting down, crashing into the ground at a 45 degree angle.

While heading back to the carrier, Cunningham and Driscoll’s Phantom was hit by a SA-2 SAM over Nam Định, 90 km (55.9 miles) southeast of Hanoi. Despite extensive damage, including both hydraulic systems, Cunningham was able to control the Phantom with the rudders, enabling him and Driscoll to stay in the crippled jet. Fire warnings sounded in the cockpit, but they worried more about becoming POWs. Every second in the cockpit brought them closer to the coast and rescue. Finally the last systems failed and the Phantom began to spin uncontrollably. To stabilize the spin, Cunningham deployed the drag chute. The radio was soon filled with pleas from others in the squadron urging them to eject. Seeing that the drag chute was useless, Cunningham ordered Driscoll to eject. Before he got out the word ‘Eje…’, Driscoll was already out of the aircraft. ShowTime 100, BuNo 155800, fell into the South China Sea minutes after achieving their niche in the history books.

Combined with their two earlier kills on January 19th and May 8th, these three kills made Cunningham and Driscoll the first US aces of the Vietnam War and the first to make all their kills with missiles.

Video: Dogfight story Vietnam May 10, 1972 Randy Duke Cunningham

Video: The Greatest Air Battle part 7

Video: The Greatest Air Battle part 9

CAG Aircraft

Prior to 20 December 1963, Carrier Air Wings were known as Carrier Air Groups (CVGs). Carrier Air Wings are what the USAF called “composite” wings. They are composed of several aircraft squadrons and detachments of various types of fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft. The commander of the air group (known as the “CAG”) was the most senior officer of the embarked squadrons and was expected to personally lead all major strike operations, coordinating the attacks of the carrier’s planes in combat. The CAG was a department head of the ship who reported to the carrier’s commanding officer. In 1963, Carrier Air Groups were renamed Wings and the commander retained the legacy title of “CAG” which continues to this day.

The modex is a number that is part of the Aircraft Visual Identification System, along with the aircraft’s tail code. It usually consists of two or three numbers that the Department of the Navy, US Navy and US Marine Corps use on aircraft to identify a squadron’s mission and a specific aircraft within a squadron.

CVW-9, Tail Code “NG”, Vietnam 1972

| Modex Number | Squadron | Aircraft Types |

|---|---|---|

| 1## | VF-96 “Fighting Falcons” | F-4J Phantoms |

| 2## | VF-92 “Silver Kings” | F-4J Phantoms |

| 3## | VA-146 “Blue Diamonds” | A-7E Corsair IIs |

| 4## | VA-147 “Argonauts” | A-7E Corsair IIs |

| 5## | VA-165 “Boomers” | A-6A / KA-6D Intruders |

| 601-604 | RVAH-11 “Checkertails” | RA-5C Vigilantes |

| 614-616 | VAQ-130 “Zappers” | EKA-3B Skywarriors |

CVW-9 made seven subsequent Vietnam deployments aboard USS Enterprise (CVN-65), USS America (CVA-66) and USS Constellation (CV-64). During each deployment, the carrier name was painted on all the aircraft in each squadron. The CVW-9 CAG in 1972 was Commander Lowell Franklin “Gus” Eggert. In 1974, Captain Eggert assumed command of the USS Constellation.

F-4J 155800 “Showtime 100” was assigned to the CVW-9 CAG. Here it is at Moffett Field on 8-9-1969 during a public air show. NAS Moffett Field is located near the south end of San Francisco Bay, northwest of San Jose, California. Moffett was the US Navy’s West Coast Lockheed P-3 Orion (four-engine, turboprop, anti-submarine and maritime surveillance aircraft) base. Note the carrier name “USS ENTERPRISE” on the upper fuselage and the civilians examining the aircraft.

This is my close up of the stars painted on the side of the fuselage. They are not MiG kills. They represent each of the squadrons and detachments in CVW-9. The meaning of the bee emblem is unknown but my guess it meant the CAG was “as busy as a bee”.

F-4Js Showtime 112 and in the background Showtime 104 (155787) flying a MiGCAP mission from USS America in 1970.

F-4J Showtime 100 from the USS America at NAF Atsugi on 10 October 1970. Naval Air Facility Atsugi is a joint Japan-US naval air base located in the cities of Yamato and Ayase in Kanagawa, Japan. In the background is the tail of Showtime 103 (155543).

F-4J Showtime 100 after the squadron commenced flight operations from the USS Constellation in November 1971. Note the Admiral Joseph C. Clifton Trophy emblem (an award that recognizes meritorious achievement by a fighter squadron while deployed aboard a carrier) on the upper fuselage just aft of the cockpit.

The left side of F-4J Showtime 100. The location and the date are unknown.

The underside of F-4J Showtime 100 on 9 February 1972.

F-4J Showtime 100 and the second aircraft F-4J Showtime 107 (155792) dropping bombs over Vietnam in 1972.

F-4J Showtime 110 (155779) was assigned to Cunningham and Driscoll. Although it carried their names on the canopy rails, it was not flown by them on any of their MiG kills.

CVW-9 wait on the after flight deck of the USS CONSTELLATION to be launched on air strikes in the Haiphong area of North Vietnam, 9 May 1972. In the center is F-4J Showtime 110 and behind it facing the camera is F-4J Showtime 112 which Cunningham and Driscoll got their first two MiG kills in.

This is my close up of photo: USN 1151725

Two F-4J Phantoms, 155799 (NG 200) of VF-92 (foreground) and 155800 “Showtime 100” (background) undergo pre-launch checks on the waist catapults of the USS Constellation.

Cunningham, using hand gestures, describes his MiG kills to his VF-96 squadron mates in the pilots ready room abroad the USS Constellation, 10 May 1972.

In June 1972, the two aces are in the Pentagon office of John William Warner III, Secretary of the Navy. In this photo, Cunningham and Driscoll are holding models of F-4 Phantoms.

This photo of Cunningham and Driscoll was taken at NAS Miramar on 5 October 1972. Note the MiG-17 silhouettes painted in red on their helmets (aka “bone domes”) and the red VPAF kill flag markings on the splitter plate behind Cunningham’s right leg.

432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing (TRW)

On 18 September 1966, the 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing was activated at Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand as a RF-4C Phantom II wing. The wing assumed the personnel, aircraft and equipment of the 6234th Tactical Fighter Wing (Provisional), which was simultaneously discontinued. It became one of the most diversified units of its size in the USAF.

Its mission was to provide intelligence information on enemy forces through tactical reconnaissance and use its fighter elements to destroy the targets earmarked by the intelligence data provided. The wing had numerous missions in the support area. The 432nd TRW accounted for more than 80 percent of all reconnaissance activity over North Vietnam. In addition to the reconnaissance mission, the 432nd also had a tactical fighter squadron component, with two (13th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 555th Tactical Fighter Squadron) F-4C/D squadrons assigned. The squadrons flew strike missions over North Vietnam.

In the fall of 1970, the 432nd was phased down as part of the overall US withdrawal from the Vietnam War. However, in 1972, tactical fighter strength was augmented by deployed Tactical Air Command CONUS (Contiguous United States) based tactical fighter squadrons attached to the 432nd in response to the North Vietnamese invasion of South Vietnam. In addition, the 421st Tactical Fighter Squadron was reassigned from Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base. During Operation Linebacker, between May and October 1972, the 432nd TRW had seven F-4 tactical fighter squadrons assigned or attached (13th, 56th, 308th, 414th, 421st, 523rd and 555th) making it the largest wing in the USAF. The five CONUS based squadrons returned to the USA in the fall of 1972.

Combat Tree

The pilots of the 432nd TFW had “an ace up their sleeve” (a poker expression). Eight of their F-4D Phantoms had the top secret APX-80 electronic set installed, known by its code name “Combat Tree” (originally named “Seek See”). Combat Tree was able to read the IFF (Identification, friend or foe) signals of the transponders built into the MiGs. The Combat Tree program began in 1968 after the acquisition of Soviet SRO-2 transponders from MiGs which the Isrealis acquired in 1967.

The VPAF (Vietnamese Peoples Air Force) used GCI (Ground Controled Intercept) to guide their MiGs into position to intercept US aircraft. To do so the Vietnamese GCI had to know the position of their own and the US aircraft at all times. To keep the two forces apart the MiG’s had to have their transponders always “on”, transmitting the needed identification. The North Vietnamese SAM and AAA radar sites also read the MiG’s IFF signals so they do not shoot down their own aircraft.

APX-80 was operated from consoles in the WSO cockpit of the Phantom. The APX-80 scope showed the MiG’s range and azimuth but not the altitude. Ranges of APX-80 detection were up to 60 miles (96.6 km). That’s because no reflection of the signal is required. The transmission is only one-way, from the interrogator to transponder. The transponder then sends its own signal back to the interrogator. All MiGs with active IFF were located, that means also those on the ground taxiing or just testing the equipment. Eventually, the North Vietnamese became aware that something was wrong and began changing the codes each day. The transponders were also set to be active only during the critical phase of the intercept or used temporary or not at all. But that did not help much. Combat Tree had an “active” mode which could be activated by pushing a button. It transmitted an signal which interrogated the MiG’s SRO-2 transponder. The MiG pilots do not know their aircraft’s transponder was being triggered.

Video: The Soviet Kremniy-2 IFF System – A Look At SRO-2 and SRZO-2 Systems.

The first eight Combat Tree F-4Ds were assigned to the 3rd TFW at Kunsan Airbase, South Korea, in March 1971. Four of them were transferred to the 432nd TRW nine months later. Secrecy surrounding the equipment initially meant that most crews were unfamiliar with the APX-80 and most crews did their APX-80 orientation in country. Their success had the other four aircraft transferred to the 432rd in January 1972. It soon became standard for at least two Combat Tree F-4Ds be in four plane MiGCAPs whenever possible. Inevitably, this hastened their attrition, and five of them had been shot down by August 1972. The Combat Tree F-4Ds had shot down 12 MiGs by then, prompting the conversion of another batch of 20 F-4Ds.

One of it main advantages was that made it possible to eliminate “blue-on-blue” (friendly fire) long range missile accidents and the chases of “bandits” that turn out to be a stray Phantom. There were still Rules of Engagement that specified how far a Combat Tree F-4D had to be from known friendly aircraft before “free fire” of its Beyond Visual Range (BVR) targets could be sanctioned. It also gave the Phantom crews greater freedom to identify MiGs without having to rely on the sometimes confusing information relayed from radar intelligence sources.

These are some known serial numbers of F-4D-29-MCs (block 29) that were equipped with Combat Tree:

65-0784 (shot down by a J-6/MiG-19 on 10 May 1972)

65-0801

66-0232

66-0267 (shot down 2 MiGs)

66-0269

66-7463 (shot down 6 MiGs)

66-7468

66-7482

66-7501 (shot down 1 MiG)

Third US Ace

USAF Captain Richard Stephen Ritchie (Pilot)

In 1968, Ritchie’s first combat tour was with the 480th TFS, 366th TFW in Da Nang. Ritchie flew the first “Fast FAC” missions in the F-4 forward air controller program and was instrumental in the implementation and success of the program. He completed 195 combat missions. In 1969, he was selected to attend the Fighter Weapons Course at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, becoming, up to that point, the Air Force Fighter Weapons School’s youngest instructor ever at age 26. He taught USAF pilots air-to-air tactics during 1970-72 until he volunteered for his second combat tour with the 555th “Triple Nickel” TFS, 432nd TRW.

| Date (1972) | WSO | Aircraft | Tail Code | Call Sign | Weapon | Kill |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 10 | Capt. C. B. DeBellevue | F-4D 66-7463 (CT) | OY | Oyster 03 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| May 31 | Capt. L. H. Pettit | F-4D 65-0801 (CT) | OY | Icebag 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| July 8 | Capt. C. B. DeBellevue | F-4E 67-0362 | ED | Paula 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| July 8 | Capt. C. B. DeBellevue | F-4E 67-0362 | ED | Paula 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| August 28 | Capt. C. B. DeBellevue | F-4D 66-7463 (CT) | OY | Buick 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

CT = Combat Tree

On July 8th while flying F-4E 67-0362 (armed with an internal M61A1 20mm cannon), Ritchie made his third and fourth kills with the long range AIM-7 Sparrow missile instead.

Ritchie’s fifth MiG kill was an exact duplicate of a syllabus mission at Fighter Weapons School which he had not only flown as a student, but had taught it about a dozen times prior to actually doing it in combat.

Ritchie was leading “Buick”flight, a MiGCAP for a strike north of Hanoi. When Ritchie had just started his flight on its return to base, Red Crown, a nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser USS Long Beach, alerted the strike force of “Blue Bandits” (MiG-21s) 30 miles (48 km) southwest of Hanoi, along the route back to Thailand. Approaching the area of the reported contact at 15,000 feet (4,600 m), Ritchie suspected the MiGs would be using high altitude tactics. Buick and Vega flights, both of the MiGCAP, flew toward the reported location.

DeBellevue picked up the MiGs on the onboard radar and using Combat Tree, discovered that the MiGs were 10 miles (16 km) behind Olds flight, another flight of MiGCAP fighters returning to base. Ritchie called in the contact to warn Olds flight. Concerned that the MiGs might be at an altitude above them, Ritchie made continuous requests for altitude readings to both EC-121 “Disco” and Red Crown. He received location, heading, and speed data on the MiGs. He determined the MiGs were returning north at high speed to their base but not at the altitude of Buick flight closing within 15 miles (24 km) of the MiGs. DeBellevue’s radar painted the MiGs straight ahead at 25,000 feet (7,600 m), and Ritchie ordered the flight to light afterburners. DeBellevue warned Ritchie they were closing fast and were in range. About the same time, Ritchie saw the MiGs heading in the opposite direction.

Attacking in a climbing curve behind the MiG-21s with his AIM-7 guidance radar locked on, Ritchie was given continuous range updates from DeBellevue. With his Phantom barely making enough speed to overtake the MiGs, Ritchie launched two Sparrow missiles from over 4 miles (6.4 km) away. Although the firing parameters of the missiles were out of their performance envelope, it was an attempt to persuade the MiGs to change their course and shorten the range. Both missiles missed but also failed to make the MiGs turn. Moments later, while tracking one MiG visually by its contrail, Ritchie fired his remaining two Sparrows, also at long range. The first Sparrow missed, but the MiG made a hard turn and had shortened the range. It was destroyed by the second Sparrow.

Ritchie (5th kill) and DeBellevue (4th kill) with F-4D 66-7463.

Video: Profiles in Valor: Brigadier General Steve Ritchie

Highest Scoring US Vietnam Ace

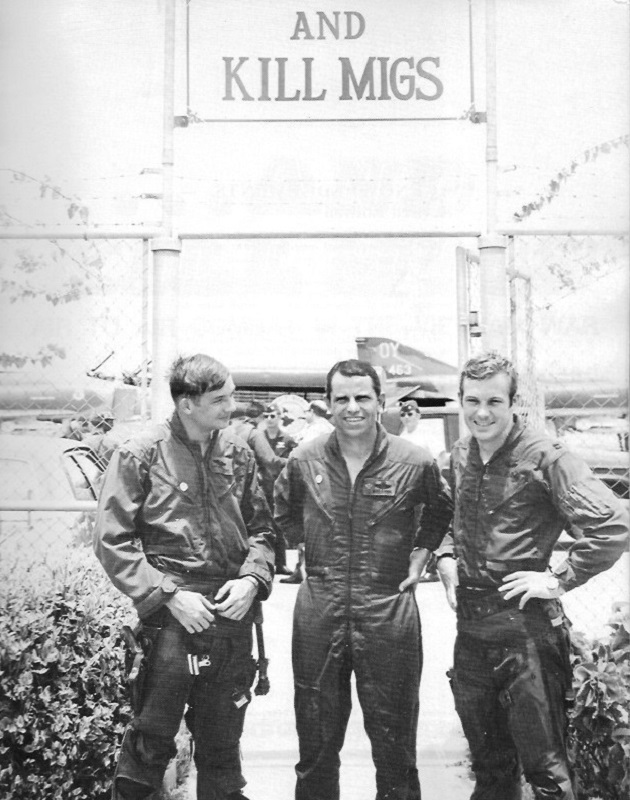

USAF Captain Charles Barbin DeBellevue (WSO)

After applying unsuccessfully to the USAF Academy, he attended and graduated from the University of Southwestern Louisiana in 1968. Upon graduation, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant through the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program at the university. Accepted into Undergraduate Pilot Training, he failed to complete the course, but subsequently applied for and was accepted into Undergraduate Navigator Training. In Vietnam, he was assign to the 555th TFS, 432nd TRW.

| Date (1972) | Pilot | Aircraft | Tail Code | Call Sign | Weapon | Kill |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 10 | Capt. R. S. Ritchie | F-4D 66-7463 (CT) | OY | Oyster 03 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| July 8 | Capt. R. S. Ritchie | F-4E 67-0362 | ED | Paula 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| July 8 | Capt. R. S. Ritchie | F-4E 67-0362 | ED | Paula 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| August 28 | Capt. R. S. Ritchie | F-4D 66-7463 (CT) | OY | Buick 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| September 9 | Capt. John A. Madden, Jr. | F-4D 66-0267 (CT) | OY | Olds 01 | AIM-9 | MiG-19 |

| September 9 | Capt. J. A. Madden | F-4D 66-0267 (CT) | OY | Olds 01 | AIM-9 | MiG-19 |

CT = Combat Tree

DeBellevue (left) and Ritchie (right) pose between Colonel Scott G. Smith, 432rd TFW commander. The two entrances of the 423rd flight line had signs over them that read, respectively: “Our Mission: Protect the force, get the pictures” and on the other entrance “And Kill MiGs”. Behind Smith’s head is the tail of F-4D 66-7463.

After becoming the highest scoring US ace, DeBellevue was sent to Williams Air Force Base, Arizona, for pilot training. He became an aircraft commander of F-4E Phantom IIs. He retired from the USAF as a Colonel in 1998, after 30 years of service.

F-4D 66-7463 was officially credited with 6 MiG kills, the highest scoring US fighter since the Korean War. Along with Captains Ritchie and DeBellevue May 10th and August 28th MiG-21 kills, these four other crews had scored these kills.

| Date (1972) | TFS | Pilot | WSO | Call Sign | Weapon | Kill |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 1 | 555th | Lt. Col. Joe W. Kittinger | 1st Lt. L. A. Hodgdon | Falcon 64 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| April 16 | 13th | Capt. F. S. Olmsted | Capt. S. Maas | Basco 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| May 8 | 13th | Maj. B. P. Crews | Capt. K. W. Jones | Galore 03 | AIM-7 | MiG-19 |

| October 15 | 523rd | Maj. I. J. McCoy | Maj. F. W. Brown | Chevy 01 | AIM-9 | MiG-21 |

F-4D 66-7463 with its 6 kill markings at Udorn in 1975. The OY tail code has been removed in preparation for transferring to another TFW.

Fifth and Last US Ace

USAF Captain Jeffrey S. Feinstein (WSO)

Feinstein, nickname “Fang”, was rejected from pilot training due to excessive myopia (near sighted). He then underwent Undergraduate Navigator Training and became a WSO and was assigned to the 13th TFS “The Panther Pack”, 432nd TRW. He was probably the only US ace who wore glasses in combat.

| Date (1972) | Pilot | Aircraft | Tail Code | Call Sign | Weapon | Kill |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 16 | Major Edward D. Cherry | F-4D 66-7550 | PN | Basco 03 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| May 31 | Capt. Bruce G. Leonard Jr. | F-4E 68-0338 | ED | Gopher 03 | AIM-9 | MiG-21 |

| July 18 | Lt. Col. Carl G. Baily | F-4D 66-0271 | OY | Snug 01 | AIM-9 | MiG-21 |

| July 29 | Lt. Col. Carl G. Baily | F-4D 66-0271 | OY | Cadillac 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

| October 13 | Lt. Col. Curtis D. Westphal | F-4D 66-7501 (CT) | OC | Olds 01 | AIM-7 | MiG-21 |

CT = Combat Tree

13th TFS Commanders:

Lt. Col. Bailey, 13 July 1972

Lt. Col. Westphal, 6 September 1972

On 25 August 1972, Lt. Col. Baily and Feinstein had to eject from their F-4D 66-7482 (CT) when it was hit by 37mm AAA at 3000 feet (914.4 meters) near Haiphong. A 37th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron (ARRS) HH-53 “Jolly Green Giant” rescue helicopter from Da Nang plucked them from the Gulf of Tonkin.

Mackay Trophy

Ritchie, DeBellevue and Feinstein were awarded the 1972 Mackay Trophy. The Mackay Trophy is awarded yearly by the USAF for the “most meritorious flight of the year” by an Air Force person, persons, or unit. The award was established on 27 January 1911 by Clarence Mackay, who was then head of the Postal Telegraph-Cable Company and the Commercial Cable Company. Originally, aviators could compete for the trophy annually under rules made each year or the War Department could award the trophy for the most meritorious flight of the year.

A couple other notable recipients of the award were:

- 1918, Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, the highest scoring US ace of WWI with 26 victories.

- 1947, Captain Chuck Yeager who was the first to break the sound barrier in the Bell X-1.

The Mackay trophy was last awarded in 2021 and it is housed in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum.

Today

Robin Olds’ F-4C Phantom II, 64-0829, SCAT XXVII, at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio.

Brigadier General Robin Olds, USAF (Retired) next to SCAT XXVII. Sadly, General Olds passed away on 14 June 2007.

Video: McDonnell Douglas F-4C Phantom II (Robin Olds F-4)

F-4J BuNo 157267 Showtime 112 did survive the war. After VF-96, it flown with VF-114, VF-21, VMFA-232, VMFA-235, and VMFA-122. In 1975, it was upgraded to a F-4S (F-4J modernized with smokeless engines). On 15 December 1984, it was transferred to the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposition Center (MASDC) also known as the “Boneyard”. It is currently on displayed at the San Diego Aerospace Museum in California since 1990.

Above and below the star and bars insignia on the fuselage are F-4S modifications which did not exist in 1972.

Video: Vietnam ACE Steve Ritchie flying F-4D Phantom II at Andrews 2000

Video: USAF Fighter Ace BG Steve Ritchie

Video: F-4D Phantom II

F-4D 66-7463 with its six MiG kills is currently on display at the United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado.

F-4D 66-0267: From 1975 to 1979, it was with the 18th TFW based at Kadena AB, Okinawa, Japan. From 1979 to 1988, 66-0267 was with the 31st TFW based at Homestead Air Force Base, Florida. On 21 March 1988, 66-0267 was withdrawn from service and re-designated as a GF-4D. At Homestead, it was assigned as a Battle Damage Repair trainer. It was damaged by Hurricane Andrew on 24 August 1992. In 1993, it was repaired with parts from other damaged Phantoms by a team of Reserve aircraft repair technicians from Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio with some parts from another F-4 displayed at the Avon Park Bombing and Gunnery Range. It was placed on a pedestal display on 4 March 1994.

F-4D 66-0267 with two MiG-19 kills (DeBellevue’s 5th and 6th) is a gate guard at the Homestead Air Force Base located in Miami–Dade County, Florida.

F-4D 66-7550 with its one MiG-21 kill (Feinstein’s first) is in Aviation Heritage Park, 1825 Three Springs Road, Bowling Green, Kentucky 42104.

Model Kits

1/48:

Hasegawa 07101 McDonnell Douglas F-4J Phantom II ‘Showtime 100’ – 1989

Zoukei-Mura SWS48-04 F-4J Phantom II – 2016

1/72:

Hasegawa 00089 F-4C/D Phantom II `MiG Killer´ – 2000

Italeri 1373 F-4 C/D/J Phantom II Aces U.S.A.F.-U.S. Navy Vietnam Aces – 2016

Doyusha 41260 USN F-4J Phantom II “Showtime 100” – 2017

Hobby 2000 72028 Vietnam Aces vol.2 – 2020

Fine Molds FP47S U.S. Air Force Jet Fighter F-4D “The First MiG Ace” – 2021

Fine Molds FF04 U.S. Navy F-4J Phantom II VF-96 ‘Showtime 100’ – 2024