Eddie Rickenbacker was a US pursuit pilot during WWI. With 26 victories, he was the most successful and most decorated US flying ace of the war which he achieved in about three months of aerial combat. After the war, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. He survived two plane crashes and spent 26 days adrift at sea. He was also a racing car driver, an automobile engineer, and a long-time head of Eastern Air Lines.

Edward Vernon Rickenbacker (8 October 1890 to 23 July 1973) was born as Edward Rickenbacher in Columbus, Ohio. He was the third of eight children born to German speaking Swiss immigrants, Lizzie (née Liesl Basler) and Wilhelm Rickenbacher. His father worked for breweries and street-paving crews and his mother Lizzie took in laundry to supplement the family income. In 1893, his father owned a construction company.

The summer before his 14th birthday, his father was injured in a brawl. A hit on the head with a level, his father was in a coma for almost six weeks before his death on 26 August 1904.

He felt a responsibility to help the family with the income. Although his two older siblings Bill and Mary were working, he dropped out of the seventh grade and went to work full-time, lying about his age to get around the child labor laws. He took any job he could find and it was through these jobs, that he landed in the growing automobile industry. This, combined with his interests in technology and speed led him to seek out automobile racing.

Rickenbacker began working with cars in Evans Garage. In 1905, He took a mechanical engineering course from the International Correspondence School, in order to become more proficient at working on cars. Later that year, he was employed by the Oscar Lear Automobile Company in Columbus, Ohio, where he worked under their Chief engineer, Lee Frayer. Frayer took him under his wing, giving him more responsibility in the workshop.

In 1907, Eddie then followed Lee Frayer to work at the Columbus Buggy Company. It was there he started his racing career, participating in the first Indianapolis 500 on 30 May 1911 as a relief driver. Rickenbacker replaced injured Frayer in the middle portion of the race, driving car number 30 the majority of the miles and helped his former boss take 13th place out of 40 cars.

He kept racing for the Columbus Buggy Company until 1912, when he left to pursue a professional racing career. He raced for the Mason Company until the end of 1914. He went on to become the manager of the Prest-O-Lite Racing Team which lasted until the end of 1916.

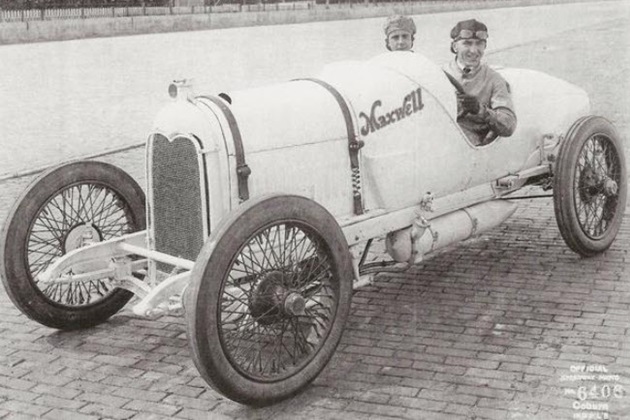

One of four Maxwell Special race cars of the 1916 Prest-O-Lite Team. Drivers: Rickenbacker (at the wheel) and Pete Henderson.

German Spy

After signing with the British Sunbeam team for the upcoming season in 1915-16, Rickenbacker sailed to England to work on developing a new race car. After his arrival at Liverpool, Rickenbacker was briefly detained by two plain clothes agents from the Metropolitan Police prior to disembarking from his ship. A 1914 Los Angeles Times article had falsely claimed that he was Baron Rickenbacher, “the disowned son of a Prussian noble.” In WWI Britain, this made the police to suspect Rickenbacker of being a German spy.

After his release, Rickenbacker worked at the Sunbeam shop in Wolverhampton during the week and spent his weekends at the Savoy Hotel in London. The Metropolitan Police surveilled Rickenbacker during the six weeks he spent in England and for another two weeks when he was back in the US. In early 1917, due to his experience as a suspected spy and in order to anglicize his name, he officially changed the spelling of his last name from “Rickenbacher” to “Rickenbacker”.

When reporting on races, the newspapers misspelled his name as Reichenbaugh, Reichenbacher, or Reichenberger, before settling on Rickenbacker. In 1915, newspapers began spelling his name with a second “k” more frequently, with his active encouragement. He also decided his given name looked a little plain so he adopted a middle initial. He signed his name 26 times with different letters before settling upon “V”.

The Sheepshead Bay Race Track was located in the eastern portion of Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York. It was originally built for horse racing in 1880 with a dirt track. After the 1908 New York state ban on gambling, it was converted to an automotive race track with a 2 mile (3.22 km) board track in 1913-14 and became the Sheepshead Bay Speedway. In 1923, the Speedway was divided into plots which were auctioned off for local real estate development.

On 13 May 1916, Rickenbacker and his riding mechanic, Clyde Latta, get ready for the start of the American Automobile Association (AAA) Metropolitan Trophy Race at Sheepshead Bay. The race was 75 laps (150 miles / 240 km) and Rickenbacker came home victorious driving the only Maxwell in a starting field of 10 cars.

The next day, the largest daily newspaper in Connecticut, the Hartford Courant, referred to him as “Edward Victor Rickenbacher” in their article on his win at Sheepshead Bay. He finally settled on his middle name to be “Vernon” after the brother of his boyhood crush, Blanche Calhoun.

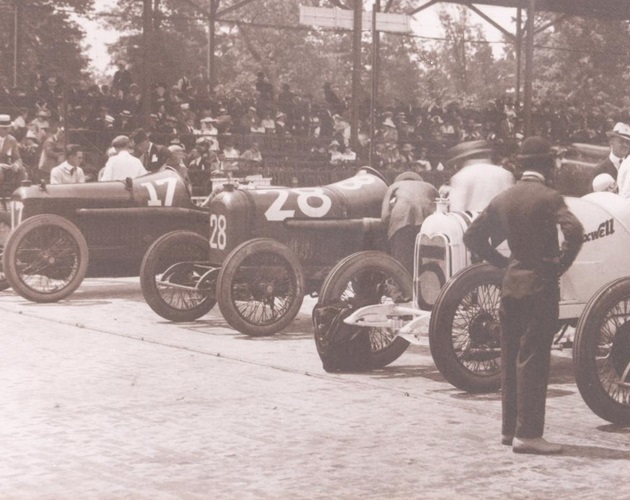

The 6th International 300-Mile Sweepstakes Race was the sixth running of the Indianapolis 500. It was held at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway on Tuesday, 30 May 1916. The management scheduled the race for 120 laps, 300 miles (480 km), the only Indianapolis 500 race scheduled for less than 500 miles (800 km). In addition to the altered distance, the start time was moved from 10:00 AM to the early afternoon (1:30 PM). The race consisted of only 21 cars, the smallest in Indy history.

This is the first row of the starting lineup of the 1916 Indianapolis 500. From far left, No. 17 was driven by Dario Resta (who won the race), No. 28 was Gil Andersen; No. 5 Eddie Rickenbacker, and No. 18 Johnny Aitken. Rickenbacker was ranked 2.

This is a close up of starting line. Note the number 5 painted on the front grill of Rickenbacker’s white Maxwell.

Rickenbacker in car 5 took the lead at the start, and led the first 9 laps until dropping out due to steering problems.

Eddie competed in 42 races over 5 years and won 7 races. Rickenbacker was a national racing figure, earning the nickname “Fast Eddie”. One sports writer called him “the most daring and…the most cautious driver in America today.”

First race:

30 May 1912 Indianapolis 500 (Indiana)

First win:

4 July 1914 Sioux City 300 (Iowa)

Last race and last win:

30 November 1916 Championship Sweepstakes (Ascot Speedway, Los Angeles, California)

WWI

While in England, Rickenbacker watched the Royal Flying Corps planes fly over the Thames from the Brooklands Aerodrome. He began to consider a role in aviation if the US entered the war. The month before, while he was in Los Angeles, Rickenbacker had two chance encounters with aviators. Glenn Martin, founder of Glenn L. Martin Company and more recently with Wright-Martin Aircraft, gave Rickenbacker his first plane ride. Next, Major Townsend F. Dodd was stranded with his plane in a field and Rickenbacker diagnosed it had a magneto problem. Major Dodd later became General John J. Pershing’s aviation officer and was an important contact in Rickenbacker’s attempt to get into aerial combat.

On 6 April 1917, the US Congress voted to declare war on Germany and the US had entered the war. In late May 1917, a week before he was to race in Cincinnati, Rickenbacker was invited to sail to England with General John J. Pershing. By mid-June, he was in France, where he was in the US infantry and assigned to drive Army officials between Paris and AEF headquarters in Chaumont, and to various points on the Western Front. Rickenbacker earned the rank of Sergeant First Class but never drove General Pershing. He mostly drove Major Dodd around.

A chance encounter with Captain James Miller on the Champs-Elysees put Rickenbacker on the right track to becoming a pursuit pilot. Miller asked Rickenbacker to be the chief engineer at the flight school and aerodrome he was establishing at Issoudun, France. Rickenbacker bargained for the chance to learn to fly at the French flight school outside of Toul. He received five weeks of training or 25 hours in the air in September 1917. Then, he went to Issoudun to start constructing the United States Air Service (USAS) pursuit training facility.

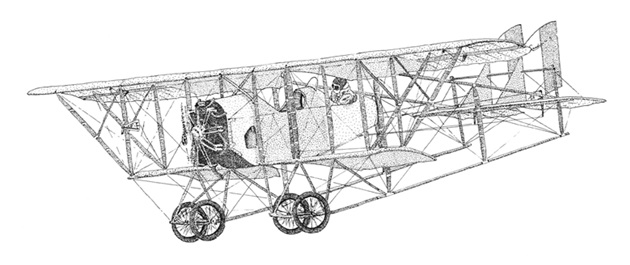

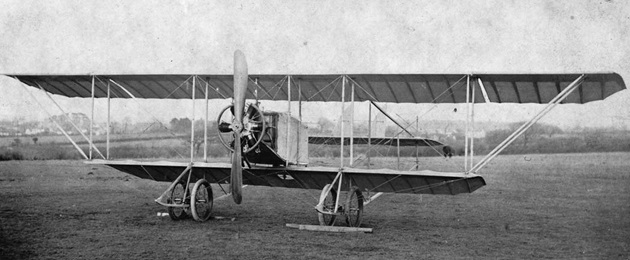

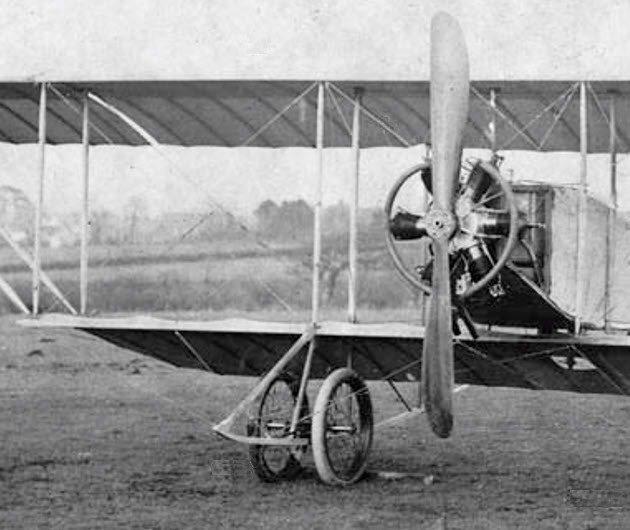

Rickenbacker standing by a Caudron G.II trainer probably at Issoudun in late 1917. Note the French Roundel on the underside of the top wing.

Rickenbacker standing in front of a Caudron G.II trainer. Note in the background on the right is the wing tips of another Caudron G.II trainer.

Only ten French Caudron G.IIs were built in 1913, with five assigned to Escadrille Caudron Monoplace 39, four delivered to the Australian Flying Corps, and the last one went to the Royal Naval Air Service.

It had a short crew nacelle, with a single engine in the nose of the nacelle, and two open tail boom trusses. Single seat and two seat versions were built. It had a sesquiplane layout and used wing warping for lateral control. The wings of the Caudron had scalloped trailing edges that were to become a trademark of the aircraft.

This is my close up of the above Caudron G.II. Compare it to the trainer Rickenbacker is standing by in the photos above.

The French used the Caudron G.II for advanced flight training before and at the start of WWI. It was determined not suited for use at the front but the good flying qualities and sturdy construction made it a good training aircraft. Its 4-wheel and skids landing gear saved many pilot’s lives during bad landings. Many French pilots made their first solo flight on this type.

Escadrille Caudron Monoplace 39 most likely provided the Caudron G.IIs to the USAS since in late 1917 they had newer and better aircraft. Later, the USAS purchased Caudron G.III trainers which entered French service in 1914. The G.III had a cowl cover over the top half of the front of the engine and it had solid dish landing wheels instead of the earlier bicycle spoked wheels.

During the last three months of 1917, Rickenbacker took time from his work schedule to continue his flight training, standing in at the back of lectures and taking airplanes up on his own to practice new maneuvers. In January 1918, Rickenbacker finagled his way into a slot for gunnery school, the final step to becoming a pursuit pilot. Rickenbacker was assigned to the newly formed US 94th Aero Squadron.

After the US entered WWI, the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was is need of aircraft but US had none available. The AEF purchased 287 French built Nieuport 28s for $18,500 each, and the first ones reached the AEF in February of 1918, without machine guns installed. The US pilots flew them without armaments until late March.

Major Raoul Lufbery was the leading ace of the Lafayette Escadrille (US volunteer pilots in a French squadron) scored 17 confirmed aerial victories. His actual number of victories has been unofficially estimated to be anywhere between 25 and 60. In late 1917, he was commissioned in the USAS with the rank of Major. In the spring of 1918, Lufbery was chosen to become the commanding officer of the US 94th Aero Squadron with the principal job to instruct the new pilots in aerial combat maneuvers.

In February and March 1918, Lieutenant Rickenbacker and the officers of the US 1st Pursuit Group completed advanced training at Villeneuve–les–Vertus Aerodrome located 3.4 miles (5.5 km) northeast of Vertus (today Blancs-Coteaux) in northeastern France. There he came under the tutelage and mentorship of the Major Lufbery. Lufbery took Rickenbacker and Douglas Campbell on their first patrol before their Nieuport 28s were outfitted with machine guns. They flew along the front lines over the Allies side getting familiar with the terrain.

On 19 May 1918, Major Lufbery’s Nieuport 28 was shot down and he was KIA. A defensive air combat maneuver, the “Lufbery circle” or “Lufbery wheel” was named after him, but he did not invent the maneuver, although it may be from him publicizing it with the pilots he trained.

Rickenbacker earned the respect of his fellow fliers who called him “Rick”.

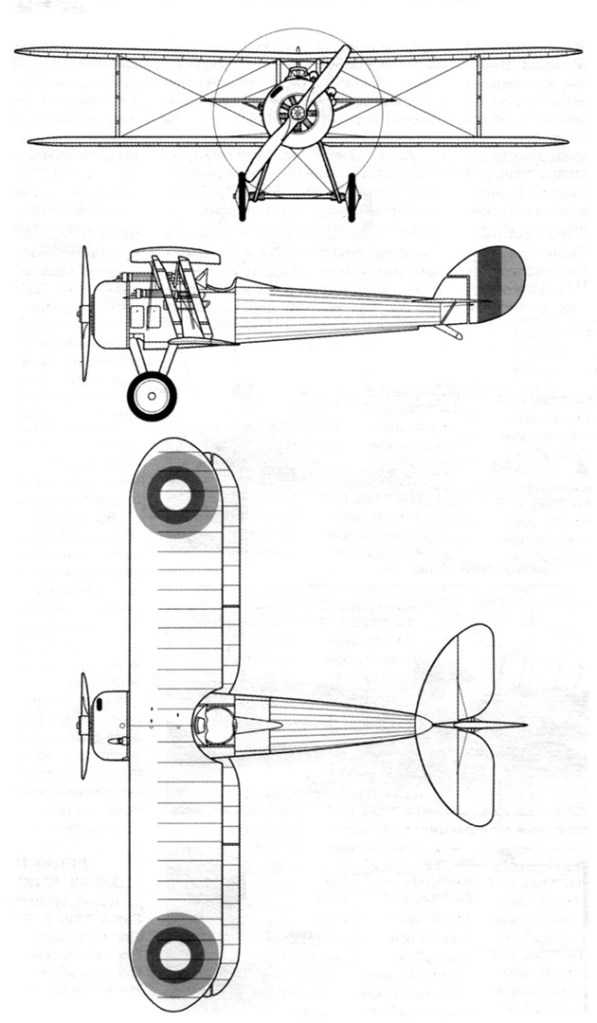

Nieuport 28

Nieuport 28 C-1, s/n 6159, Plane Number 12 was assigned to First Lieutenant Rickenbacker. The US squadrons carried French Roundels on their planes in France 1917-18.

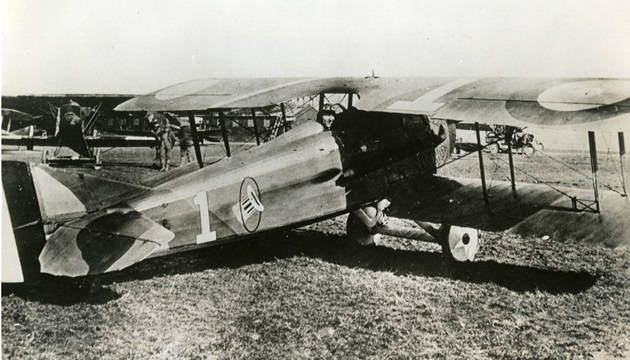

The 94th Aero Squadron “Hat in the Ring” was ordered to proceed to Croix de Metz Aerodrome in the US sector of the line on April 7th and was assigned to support the Eighth French Army. It was the first trained and organized US pursuit squadron to be stationed at the front and see active combat service.

The Toul-Croix De Metz Airdrome was located approximately one mile (1.6 km) northeast of Toul and 160 miles (260 km) east of Paris. It was established by the French Air Force as early as 1912 and was turned over to the AEF in April 1918.

Photos of Rickenbacker’s Nieuport 28 number 12 at Toul-Croix de Metz Aerodrome.

These two photos have a good view of the machine guns mounted.

Rickenbacker standing beside Nieuport 28 number 5 at Toul-Croix De Metz on May 5th, two days before he got his second victory. Another unidentified pilot of the 94th Squadron was also photographed standing next to this plane. No information is found of which pilot this plane was assigned to or if Rickenbacker had flown it.

On 30 May 1918, he achieved his sixth victory, but it would be his last for about three and a half months. In mid-June 1918 , Rickenbacker officially became the second ace in US history.

On 29 June 1918, the US 1st Pursuit Group moved to the Chateau Thierry sector and to Touquin Aerodrome. There, the 94th Aero Squadron and the other squadrons of the 1st Pursuit had converted from their agile but temperamental Nieuport 28s to the more rugged, higher-powered SPAD XIII.

In late June 1918, Rickenbacker had a fever and an inner ear infection that turned into an abscess and he was grounded. Rickenbacker recovered in a Paris hospital during the month of July. Rickenbacker was out of the hospital in time for the St. Mihiel offensive and was at the Rembercourt Aerodrome on 12 September 1918.

Rembercourt Aerodrome was a temporary WWI airfield in France. It was located 1.6 miles (2.6 km) east-northeast of Rembercourt aux Pots, today part of Rembercourt-Sommaisne, in northeastern France. The airfield was built and used by the French Air Service at Rembercourt in early 1916 and again in August 1918, before it was transferred to the USAS in early September 1918.

Although Rickenbacker’s aerial performance was rising, the 94th Squadron’s performance was disappointing. After a sluggish summer at Chateau Thierry, Major Harold Evans Hartney (commander of the US 1st Pursuit Group) wanted new leadership to lead the 94th Squadron to its former greatness. He chose First Lieutenant Rickenbacker over several captains as the new commander of the squadron and Rickenbacker was promoted to Captain.

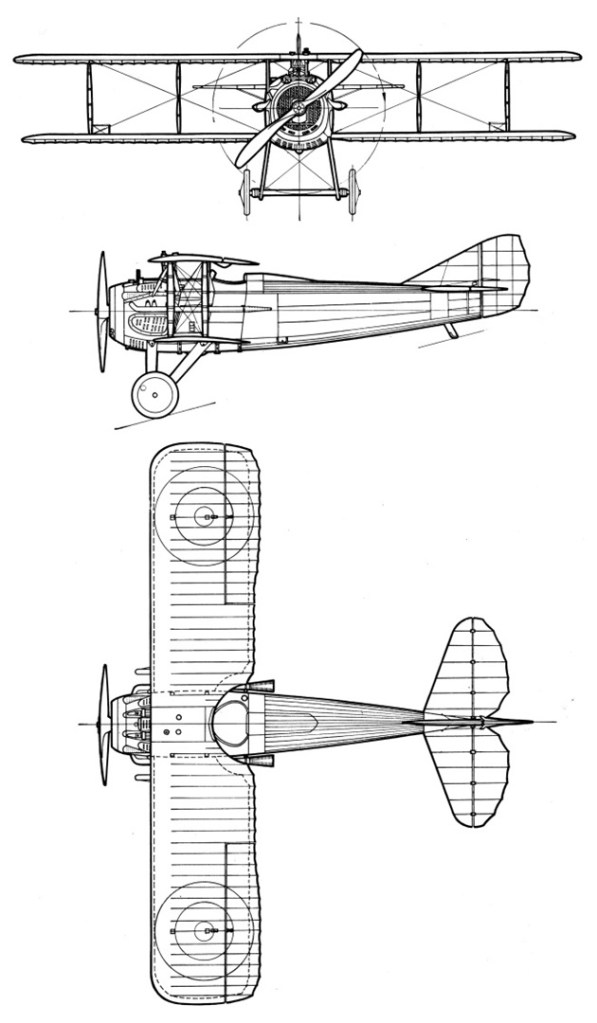

SPAD XIII

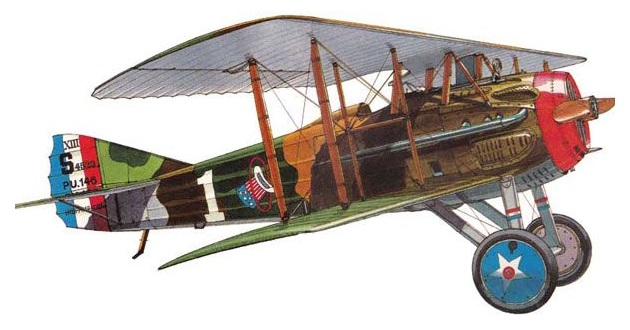

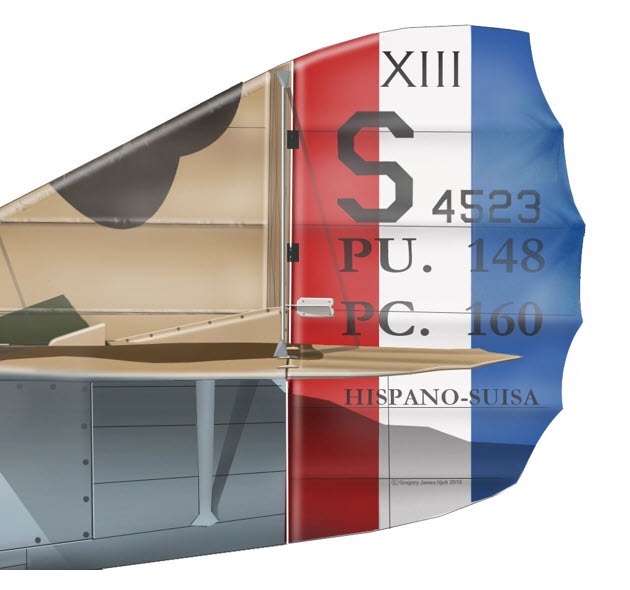

SPAD S.XIII, s/n 4523, Plane Number 1 was assigned to Captain Rickenbacker.

This is my close up of the markings on the tail of Rickenbacker’s SPAD XIII.

“PU” stands for “Poids Utile” in French, which translates to “Useful Load”. It refers to the maximum load capacity of the plane, indicating the weight that can be safely carried or supported (the pilot and his equipment). PU. 148 kg (326.3 Lbs.)

“PC” stands for “Poids Combustible” in French, which translates to “Combustibles Weight”. It refers to the weight of fuel for a typical mission, not necessarily maximum capacity. PC. 160 kg (352.7 Lbs.) 160 kg of gasoline is approximately 211.12 liters (55.77 gallons).

Hispano-Suiza is the 150 hp, V-8 water-cooled aircraft engine.

Rickenbacker standing next to his assigned SPAD XIII in September 1918 after returning from the hospital. Note he is holding a cane. His inner ear infection affected his sense of balance and he still needed the cane for a short time.

Rickenbacker in flight gear standing by his dirty SPAD XIII. Note the large number 1 on the lower left wing and the roundel underneath the right wing.

Well known photo of Rickenbacker in uniform posing by his cleaned and repainted SPAD XIII most likely for the newspapers.

Rickenbacker’s most remarkable action came on 25 September 1918, as Rickenbacker patrolled alone near Billy (northeast of Verdun, today Billy-sous-Mangiennes). He spotted a group of seven enemy aircraft, and despite being out numbered, he boldly attacked and shot down two of them. In 1931, US President Herbert Hoover awarded Rickenbacker the Medal of Honor for his aggressiveness in this action.

Rickenbacker flying over the Grand Est (“Greater East”) region (east of Paris) in October 1918.

Artwork of Rickenbacker’s SPAD XIII shooting down a red German biplane, most likely an observation plane due to the rear machine gun.

October 2nd

On 2 October 1918, Rickenbacker and Reed Chambers forced down a Hannover CL.IIIA near Montfaucon (today Montfaucon-d’Argonne, northwest of Verdun). The two-seat, single-bay biplane belonged to Schlachtstaffeln Nr. 20 (Schlasta 20) which was one of the specialized fighter-bomber squadrons in the German Luftstreitkräfte (Air Force). A Schlasta usually consisted of 4-6 aircraft which was the maximum number a formation leader could effectively command without voice radio.

The Hannover CL.IIIA entered service in early 1918 and it was used to escort reconnaissance aircraft and as a ground-attack fighter. The CL.IIIA had a 180-HP (130 kW) Argus As.III engine instead of the water-cooled 160-HP (120 kW) Mercedes D.III straight-six engine which the CL.III had.

This is my close up of the above photo. The text on the fuselage between the crosses is “Trophy of Pursuit Group – Han. C.L. III A 3802/18”. The 18 at the end of the serial number was most likely the year.

Rickenbacker posing next to the Hannover CL.IIIA. The text is “Shot down by CAPT. E.V .RICKENBACKER & LT. REED CHAMBERS, 94th Aero Squadron, OCT. 2nd 1918”. Note it appears that the Rickenbacker’s middle initial was changed. There is a space after the “V” and then a period.

Rickenbacker (on the left) standing next to another Hannover CL.IIIA from Schlasta 20 that was shot down but not by him. Note number 4 on the forward fuselage. The officer on the right most likely a squadron mate, his name is not known.

Hannover CL.IIIA number 4, s/n 3892/18, was shot down on October 4th by US machine gun ground fire and force landed near Montfaucon. The number 4 is to the right of the landing wheels and it has the same arrow painted on the fuselage side. It appears upon landing the plane managed to hit the only post in the field and nosed over.

Rickenbacker learned that the best way to take down enemy planes was to sneak up on them. Once he determined their position, he came down from above with the sun behind him. The enemy didn’t see him until it was too late. By the time they could react, he was out of sight and was getting ready for another attack run.

On 10 October 1918 near or over Cléry-le-Petit (northwest of Verdun), Rickenbacker got his 19th and 20th victories, two Fokker D.VIIs. Both victories were recorded at the same time at 1552 hours. He dived on a pair of Fokker D.VIIs and his machine gun fire strafed both of them in the single pass.

His skills were not without risks. He returned from one mission with a fuselage riddled with bullet holes and half of a propeller. On another mission, a bullet grazed his helmet.

Rickenbacker in his SPAD S.XIII at Rembercourt Aerodrome on 18 October 1918.

Film: Activities of the 94th Aero Squadron (France) [1918]

Film: Captains J. A. Meissner and Eddie Rickenbacker seated in their airborne aircraft.

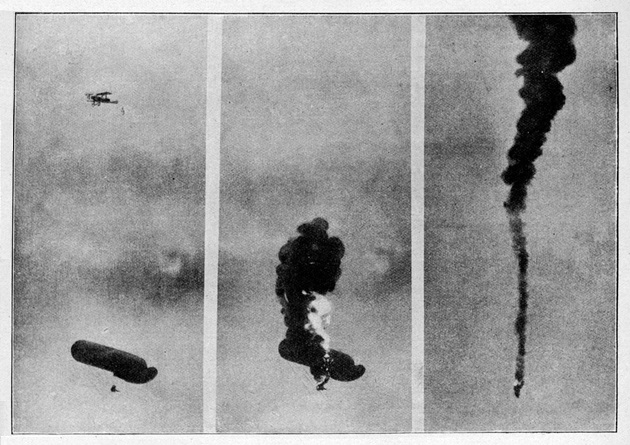

Balloon Ace

Rickenbacker also claimed five Balloon victories becoming a Balloon Ace. There were 77 US Balloon Aces during the war.

Observation balloons were consequently targets of great importance on both sides, especially before any sort of offensive, so individual pilots, flights or whole squadrons were frequently ordered to attack balloons, to destroy them or at least disrupt their observation activities.

The Parseval-Sigsfeld Drachenballon was a German observation balloon designed to replace the older spherical type balloons used for nearly a century. The spherical type balloons twirled when it was windy. The Drachenballon (“Dragon balloon”) was designed in such a way that it would stay stationary in strong wind, and was more stable over its predecessors, using design attributes similar to kites.

Due to their importance, balloons were usually given heavy defenses in the form of machine gun positions on the ground, anti-aircraft artillery, and fighter patrols stationed overhead. Other defenses included surrounding the main balloon with barrage balloons; stringing cables in the air in the vicinity of the balloons; equipping observers with machine guns; and flying balloons with explosives that could be remotely detonated from the ground. These defensive measures made balloons a very dangerous target to attack.

Pilots in WWI faced “Archy” (Flak) which consisted of black or white puffs of smoke from exploding shells. Rickenbacker was known for his “calculated caution,” often flew through these barrages to reach his targets.

The 8.8cm FlaK 16 (8.8cm K.Zugflak L/45) anti-aircraft gun was introduced in 1917 using the 88mm caliber, common with the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial German Navy) guns. Only 169 were built. It was the predecessor of the 8.8cm FlaK 18/36/37/41 guns of the 1930s and WWII.

Commonwealth troops captured this Flak 16 gun in August 1918.

The 8.8cm Flak 16 gun was towed by a Krupp-Daimler KD1 Kraftzugmaschine (Tractor unit). There was also a balloon-tractor version, which was equipped with a special winch for tethered balloons. Popularly, the vehicle was called a “Kraftzugprotze” (motorized tow vehicle) , “Motorpferd” (motorized horse) , or “Motormaulesel” (motorized mule).

There is no information indicating the Germans used the 8.8cm Flak 16 gun against WWI Allied tanks.

Although balloons were occasionally shot down by small arms fire, generally it was difficult to shoot down a balloon with solid bullets, particularly at the distances and altitude involved. Ordinary bullets would pass relatively harmlessly through the hydrogen gas bag, merely puncturing the fabric. It was not until special Pomeroy incendiary bullets and Buckingham flat-nosed incendiary bullets became available on the Western Front in 1917 that any consistent degree of success was achieved.

Pilots tried to attack from a height and angle that could enable them to fire without getting too close to the blast and pull away fast. They were also cautioned not to go below 1000 feet (300 meters) in order to avoid ground fire.

Film: IWM 164

Victory Claims

The US Army Air Service adopted the French standards for confirming victory claims. Since there were no gun cameras, the claim was confirmed if the enemy aircraft was independently witnessed:

- disintegrating while in flight

- falling in flames

- crashing to the ground

Or an enemy aircraft fell into captivity behind the Allied battle lines.

In all, Rickenbacker flew 134 combat missions and has 26 confirmed aerial victories which included 4 shared and 5 balloons.

| # | Date | Time | Aircraft | Opponent | Battle Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29 April 1918 | 1810 | Nieuport 28 | Pfalz D.III | Baussant |

| 2 | 7 May 1918 | 0805 | Nieuport 28 | Pfalz D.III | Pont-à-Mousson |

| 3 | 17 May 1918 | 1824 | Nieuport 28 | Albatros D.V | Ribécourt |

| 4 | 22 May 1918 | 0912 | Nieuport 28 | Albatros D.V | Flirey |

| 5 | 28 May 1918 | 0925 | Nieuport 28 | Albatros C.I | Bois de Rate |

| 6 | 30 May 1918 | 0738 | Nieuport 28 | Albatros C.I | Jaulny |

| 7 | 14 September 1918 | 0810 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Villecey |

| 8 | 15 September 1918 | 0815 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Bois de Waville |

| 9 | 25 September 1918 | 0840 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Billy |

| 10 | 25 September 1918 | 0850 | SPAD XIII | Halberstadt C.I | Forêt de Spincourt |

| 11 | 26 September 1918 | 0600 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Damvillers |

| 12 | 28 September 1918 | 0500 | SPAD XIII | Balloon | Sivry-sur-Meuse |

| 13 | 1 October 1918 | 1930 | SPAD XIII | Balloon | Puzieux |

| 14 | 2 October 1918 | 1730 | SPAD XIII | Hannover CL.IIIA | Montfaucon |

| 15 | 2 October 1918 | 1740 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Vilosnes |

| 16 | 3 October 1918 | 1640 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Cléry-le-Grand |

| 17 | 3 October 1918 | 1707 | SPAD XIII | Balloon | Dannevoux |

| 18 | 9 October 1918 | 1552 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Dun-sur-Meuse |

| 19 | 10 October 1918 | 1552 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Cléry-le-Petit |

| 20 | 10 October 1918 | 1552 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Cléry-le-Petit |

| 21 | 22 October 1918 | 1555 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Cléry-le-Petit |

| 22 | 23 October 1918 | 1655 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Grande Carne Ferme |

| 23 | 27 October 1918 | 1450 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Grandpré |

| 24 | 27 October 1918 | 1505 | SPAD XIII | Fokker D.VII | Bois de Money |

| 25 | 27 October 1918 | 1635 | SPAD XIII | Balloon | Saint-Juvin |

| 26 | 30 October 1918 | 1040 | SPAD XIII | Balloon | Remoiville |

Awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for action:

- Near Montsec on 29 April 1918.

- Near Billy on 25 September 1918 (replaced by Medal of Honor).

Awarded a Distinguished Service Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster for action:

- Over Richecourt on 17 May 1918.

- Over Saint-Mihiel on 22 May 1918.

- Over Boise Rate on 28 May 1918.

- At 4000 meters (13000 ft) over Jaulny on 30 May 1918.

- Near Villecy on 14 September 1918.

- In the region of Bois de Wavrille on 15 September 1918.

War Hero

Rickenbacker returned home as a war hero. At the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City, 600 people, including Secretary of War Newton Baker and his mother, shuttled in from Columbus, Ohio. The crowds cheered him and toasted him and shouted and sang to him. On the streets, he was mobbed by souvenir seekers who tore buttons and ribbons off his uniform.

Rickenbacker turned down several endorsement offers and an opportunity to star in a feature film. He said producer Carl Laemmle shoved a hundred-thousand-dollar certified check under his nose. He turned down these opportunities because he did not want to cheapen his image. He did signed a book deal worth $25,000, publishing his memoirs of the war, “Fighting the Flying Circus”. Rickenbacker also contracted for a speaking tour for $10,000; still in the Army, he also used this tour to promote liberty bonds.

Captain Rickenbacker riding as a honored guest in a parade in Tacoma, Washington, a port city roughly 30 miles (48 km) from Seattle . Note the officer sitting next to Rickenbacker and the roundels painted on the wheels.

After the Liberty Bond tour, he was promoted to major, and released from the US Army in November 1919. However, he felt the rank of captain was the only one that he earned and deserved, and he preferred to be referred to as “Captain Eddie” or just “the Captain” for the rest of his life.

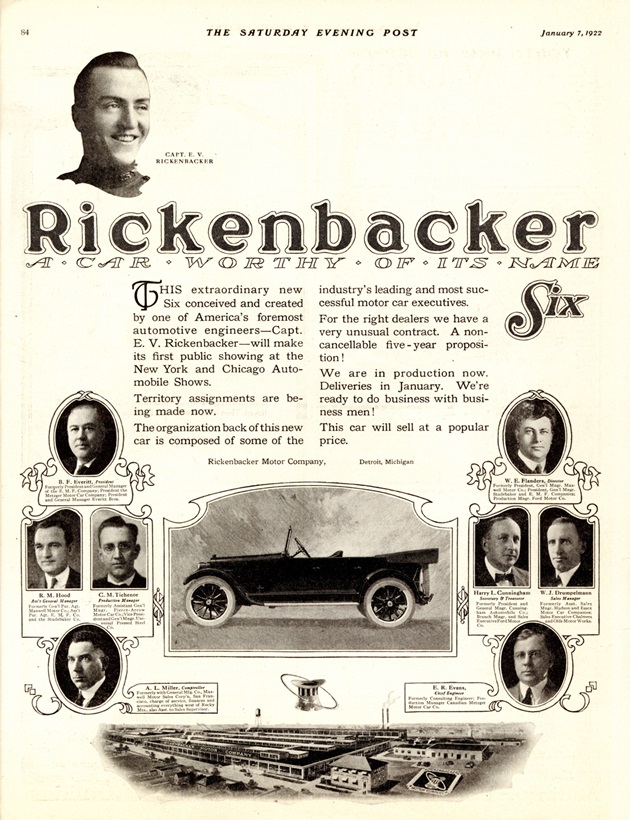

Rickenbacker Motor Company

In October 1919, Rickenbacker accepted an offer from millionaire Byron F. Everitt of Everitt-Metzger-Flanders to develop a new car under the name Rickenbacker Motor Company (RMC). His other partners in the business were Harry Cunningham and Walter Flanders.

RMC manufactured high quality cars in Detroit, Michigan, from 1922 until 1927. Rickenbacker served as Vice President and Director of Sales. The company built sporting coupes, touring cars, sedans, and roadsters. Four-wheel inside brakes were introduced in 1923. Prices in 1923 ranged from $1,485 for a phaeton to $1,985 for a sedan.

A 1925 Rickenbacker D6 Sedan with a 4,401cc eight-cylinder engine that developed 80 HP.

Rickenbacker used the WWI 94th Aero Squadron “Hat in a Ring” emblem and it was located on the front and rear on all the cars.

In 1925, Rickenbacker was a defense witness, along with Hap Arnold, Carl Spaatz, Ira Eaker, and Fiorello H. La Guardia, in the court-martial of General Billy Mitchell.

Rickenbacker resigned from RMC in 1926 due to internal disagreements with the company’s leadership. New car models were released in 1927 but the prices had increased and sales were poor. Before the company closed due to bankruptcy in 1927, 27419 cars had been built. The company’s manufacturing equipment was sold to Audi and was transported to Germany, which was somewhat ironic since Rickenbacker renounced his supposed German heritage.

Florida Airways

When he was supposed to be focusing on RMC, Rickenbacker tried to achieve speed and distance records in aviation across the United States. His focus shifted to creating a light plane that would be affordable for private ownership. In January 1923, he announced the Glider Trophy, an annual worldwide contest he established to encourage experimentation with glider design. The Trophy costed $5,000 to produce.

On 1 June 1926, Rickenbacker started Florida Airways, with wartime squadron mate Reed Chambers. Investors in the company included Henry Ford, Richard C. Hoyt of the Hayden, Stone & Co. financial empire, and Percy Rockefeller. Ford’s investment included providing three new Stout 2-AT Pullman airplanes.

Two Stout 2-AT Pullmans with Florida Airways markings on a field in Florida. Under the wings on the fuselage is “US MAIL”.

Florida Airways began carrying airmail in June 1926 and passengers two months later, flying between Miami and Jacksonville. However, Florida Airways was out of business before completing a full year of operation. It was a victim of the 1926 hurricane, the decline of the Florida real estate boom, and the failure of Tampa officials to provide the promised airport. The company was purchased from receivership by Harold Pitcairn. Pitcairn founded Pitcairn Aviation (later to become Eastern Air Lines).

Indianapolis Motor Speedway

On 1 November 1927, Rickenbacker purchased the Indianapolis Motor Speedway from Carl Graham Fisher for $700,000. He considered his salary of $5,000 a year and the opportunities for public relations to be more valuable than the $700,000 debt he incurred.

He drove the speedway’s pace car for several years. He operated the speedway for more than ten years, overseeing many improvements to the facility. He was responsible for the first national radio coverage of the Memorial Day 500 race on 30 May 1928. NBC radio covered the final hour of the race live, with Graham McNamee as the anchor.

Rickenbacker and race officials in the pace car of the 13th Indianapolis 500 race on 30 May 1925 (before he purchased the speedway). The pace car is a new 1925 Rickenbacker Vertical Eight Superfine convertible. The text “OFFICIAL PACEMAKER” is painted on the side of the hood (Bonnet). Eddie is holding a chart or board against the steering wheel probably with the race cars information.

Amelia Earhart served as the first woman referee for the 500-mile race, and was the first woman to receive an official position in the running of the annual race. Rickenbacker and Earhart at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway on 30 May 1935. On 2 July 1937, Amelia disappeared over the Pacific Ocean while attempting to become the first female pilot to circumnavigate the world.

After a final 500-mile (800 km) race in 1941, he closed the speedway to conserve gasoline, oil, rubber, and other resources during WWII. In 1945, Rickenbacker sold the speedway to businessman Anton Hulman Jr.

General Motors

Before going to Detroit to produce his automobile with RMC, Rickenbacker took a job with General Motors (GM) as the California distributor for its new car, the Sheridan. He spent the first eight months of 1921 in California, creating a network of dealerships. He often traveled between cities by plane, a leased Bellanca. In January 1928, Rickenbacker became assistant general manager for sales at GM for its Cadillac and LaSalle models.

By mid-1929, Rickenbacker returned his focus to aviation. He convinced GM to purchase Fokker Aircraft Corporation of America (FACA), the designer of the fighter planes he once faced in 1918. Rickenbacker was promoted to vice president for sales for GM’s Fokker Aircraft Company. When Fokker Aircraft relocated its headquarters to Baltimore in 1932, Rickenbacker left GM. He became the vice president for governmental relations for American Airways, part of American Air Transport. While there, he tried to convince American Air Transport to purchase North American Aviation but it never happened.

Ten months later, he left American Air Transport and returned to GM, convincing the automaker to purchase North American Aviation. When the deal went through in June 1933, Rickenbacker became vice president of public affairs in GM’s new aviation venture. North American Aviation was the parent company for Eastern Air Transport, Curtiss-Wright Corporation, and Trans World Airlines.

On 8 November 1934, Rickenbacker landed a big twin engine Douglas DC-2 transport plane at the Newark aerodrome in New Jersey from Los Angeles, California, setting a transcontinental flight record of 12 hours 4 minutes for transport planes. The old record, which was also held by Rickenbacker, was 13 hours, 2 minutes.

The underside view of the fuselage of Rickenbacker’s Douglas DC-2 at Newark, New Jersey.

Eastern Air Lines

Rickenbacker called upon his connections to achieve a merger of Eastern Air Transport with Florida Airways, forming Eastern Air Lines. He became general manager of Eastern Air Lines in early 1935.

Rickenbacker greeting Mrs. Edith Wilson (ex-First Lady, 1915-21) completing her first extended plane (DC-2) trip on 17 January 1935.

After learning that GM was considering selling Eastern Air Lines to businessman John Daniel Hertz, Rickenbacker met with GM’s chairman of the board, Alfred Pritchard Sloan, and bought the company for $3.5 million in April 1938.

Under his leadership, Eastern Air Lines was turned into a major airline. He made many radical changes in the field of commercial aviation. He negotiated with the US government to acquire air mail routes, a great advantage to companies that needed regular income.

One of the most significant transformations was related to the fleet. Ten new Douglas DC-2s were ordered to replace the existing Condors, Stinsons, Curtiss Kingbirds, and Pitcairn Mailwings.

He helped develop and support new aircraft designs. He bought larger and faster airliners, including the four-engine Lockheed Constellation and Douglas DC-4. He also collaborated with pioneers of aviation design, including Donald W. Douglas, the founder of the Douglas Aircraft Company and the designer and builder of the DC-4, DC-6, DC-7, and DC-8 (its first jet airliner).

Comic Strips

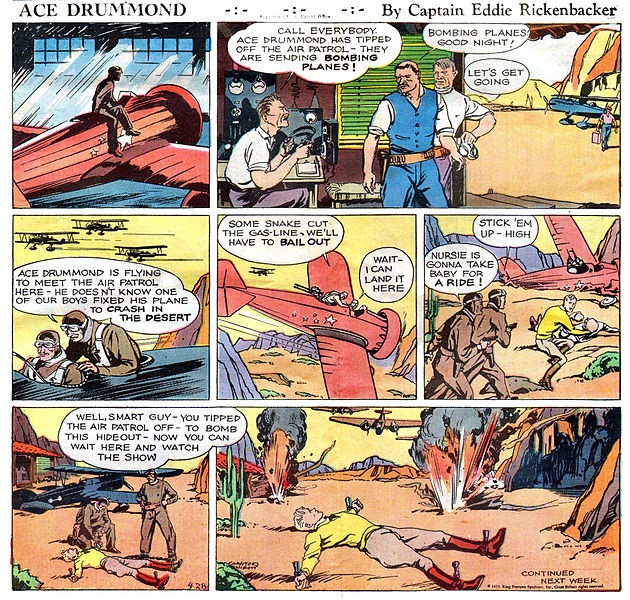

Rickenbacker scripted a popular Sunday comic strip, “Ace Drummond”, from 1935 to 1940 for King Features Syndicate. He worked with aviation artist and author Clayton Knight, who illustrated the series. The strip followed the adventures of barnstormer Drummond as he traveled around the world and defeated evil doers.

The comic was cross-promoted through Rickenbacker’s Junior Pilots Club which distributed buttons featuring Ace Drummond characters. Ace Drummond was adapted into a film serial, a radio program, and a Big Little Book titled “Ace Drummond” (Whitman Publishing Company, 1935).

Ace Drummond comic strip on 28 April 1935.

Rickenbacker and Knight created another Sunday comic strip for King Features named “The Hall of Fame of the Air”. This fact-based comic strip featured airplanes and air battles of famous aviators and aces of WWI. This comic strip was also adapted into a Big Little Book titled “Hall of Fame of the Air” by the Whitman Publishing Company in 1936.

After reading these comics, many teenage boys probably became fighter pilots in WWII.

Plane Crash

On 26 February 1941 at 11:50 PM (CST), Eastern Air Lines Flight 21, registration NC28394, was a Douglas Sleeper Transport (DST) that crashed while preparing to land at Candler Field (today Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport) in Atlanta, Georgia. Half of the 16 on board were killed, including Maryland Congressman William Devereux Byron II. Rickenbacker was among the injured and he was barely alive. Soaked in fuel, he was trapped in the wreckage overnight. The press mistakenly announced his death.

Beginning operating scheduled service with Eastern Airlines in 1936, the DST was a DC-3 commercial airliner with 14-16 sleeping berths, uppers and lowers. The sleeping berths probably did not have safety belts.

The crash site of Eastern Air Lines Flight 21 on February 27th. The plane crashed through a forest where trees sheared off the wings and the plane broke apart. The wreckage in this photo is the rear fuselage section and the tail in an upside down position.

While Rickenbacker was still conscious and in terrible pain, he was left behind while some ambulances carried away the bodies of the dead. When he arrived at the hospital, his injuries were so severe that the emergency surgeons and physicians left him for dead for some time. The doctors instructed their assistants to “take care of the live ones”.

Rickenbacker’s injuries included a fractured skull, a shattered left elbow with a crushed nerve, a paralyzed left hand, several broken ribs, a crushed hip socket, a pelvis broken in two places, a severed nerve in his left hip, a broken left knee, and his left eyeball was out of its socket. He was in critical condition at Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital for ten days.

Rickenbacker recovering from his supposedly “fatal” injuries in a hospital bed in Atlanta, Georgia after 27 February 1941.

After four months in the hospital, Rickenbacker was released. After months of home care, his injuries healed and he regained his full eyesight.

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), the predecessor of the NTSB, issued the following statement as to the probable cause:

On the basis of the foregoing findings and the entire record available to us at this time, we find that the probable cause of the accident to NC28394 (Eastern Air Lines Trip 21) on February 26, 1941, was the failure of the captain in charge of the flight to exercise the proper degree of care by not checking his altimeters to determine whether both were correctly set and properly functioning before commencing his landing approach. A substantial contributing factor was the absence of an established uniform cockpit procedure on Eastern Air Lines by which both the captain and pilot are required to make a complete check of the controls and instruments during landing operations.

WWII

During WWII, Rickenbacker toured training bases in the southwestern US and in England. He encouraged the American public to contribute time and resources and pledged Eastern Air Lines equipment and personnel for use in military activities. Under Rickenbacker’s direction, Eastern Air Lines flew munitions and supplies across the Atlantic to the British.

In 1942, with a letter of authorization from Henry L. Stimson, US Secretary of War, Rickenbacker visited England on an official war mission. He inspected troops, operations, and equipment, serving in a publicity role to increase support from civilians and soldiers. Later, he worked with both the RAF and the USAAF on bombing strategy, including work with Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris and US General Carl Andrew Spaatz.

In 1943, Rickenbacker went on a fact-finding mission in the Soviet Union to provide the Soviets with technical assistance with their Lend Lease US aircraft and to tour their aircraft factories and air defense system. He was accompanied by his doctor, Alexander Dahl of Atlanta, who gave him osteopathic treatments at least once daily.

The Soviets lavishly entertained him and there were attempts by NKVD agents to get him intoxicated enough to disclose sensitive information. He also attended ceremonies at which US medals were presented to Soviet soldiers and sailors. Rickenbacker met the foreign press in off-the-record conferences in which he talked with gracious charm, but gave no information about his mission.

After Rickenbacker returned from the Soviet Union, British prime minister Winston Churchill interviewed him. In the US, his information resulted in some diplomatic and military action, but President Roosevelt did not meet with him.

Rickenbacker posing next to a lend lease C-87 cargo plane in Russia, 1943. The Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express was an unarmed transport derivative of the B-24 Liberator heavy bomber. Above the “Hat in the Ring” emblem on the fuselage, “EDDIE RICKENBACKER” is written in Cyrillic script. To the left of Eddie’s head, a US marking was over-painted by the Russians.

For his support for the war effort, Rickenbacker received the Medal for Merit from the US government.

Adrift at Sea

In October 1942, Stimson sent Rickenbacker on a tour of air bases in the Pacific to review living conditions and operations. In addition, he was to deliver a secret message from President Roosevelt to General Douglas MacArthur.

After visiting several air and sea bases in Hawaii, Rickenbacker was provided with a B-17D Flying Fortress (no dorsal gun turret behind the cockpit) as transportation to the South Pacific. Due to faulty navigation equipment, the bomber strayed off course while on its way to a refueling stop on Canton Island, an atoll located roughly halfway between Hawaii and Fiji. When the airplane ran out of fuel, the pilot was forced to ditch the airplane in a remote part of the Pacific around October 21st.

For 24 days, Rickenbacker (age 52), US Army Captain Hans C. Adamson (his friend and business partner), and six crewmen drifted at sea in three life rafts. Adamson sustained serious injuries during the ditching. The other crewmen were hurt to varying degrees.

Rickenbacker was in a business suit with shirt and tie and his felt hat. Most of the others had shed practically everything, including their shoes, expecting to have to swim after the crash. In his five-man raft, Rickenbacker’s 185-pound frame, Adamson’s 200 pounds and Private John F. Bartek (flight engineer) were wedged into a usable area measuring 9 feet by 5 feet (2.7 meters by 1.5 meters) .

Their food supply ran out after three days. On the eighth day, a tern (seabird) landed on Rickenbacker’s head. He caught it, and the bird became both a meal for the men and fishing bait. They survived on sporadic rainwater and small fish that they caught with their bare hands. While suffering from dehydration, one of the crewmen drank seawater. He died after two weeks and was buried at sea.

On 12 November 1942, a US Navy patrol plane spotted the raft carrying Rickenbacker and the two other men in the Ellice Island chain (today Tuvalu). They were the last three survivors to be rescued.

The patrol plane which rescue them was “THE BUG”, a Vought OS2U-3 Kingfisher catapult-launched floatplane, BuNo 5308, crewed by Lieutenant (jg) William Fisher Eadie and Radioman Second Class Lester H. Boutte. It belonged to Scouting Squadron 1, Detachment 14 (VS-1, D-14 and VS-1-D14), assigned to US Marine Corps Air Group 13 based at Tutuila, American Samoa, on 22 April 1942. The aircraft of Scouting Squadron 1 were split between two other erislands, Wallis and Funafuti, 450 miles (724.2 km) apart and both are more than 700 miles (1126.54 km) from Tutuila.

The Bug belonged to VS-1-D14 and was based at Funafuti Island.

This is my close up of the nose of the Kingfisher in the above photo which shows the location of the name.

Note:

The Bug was one of three float planes on the battleship USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) which was in dry dock at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. The Pennsylvania and the Bug suffered minor damage during the Japanese attack.

Lieutenant Eadie landed his Kingfisher and picked up the survivors. The weak and injured Adamson was put in Boutte’s back seat. Rickenbacker and Bartek were tied together and they sat on the wing outside the cockpit, one on each side. Boutte stood on the wing and held them by the collar of their shirts. A Kingfisher could not take off with such a load, so Eadie started taxiing on the water back to their base on Funafuti, about 40 miles (64.4 km) distance.

After taxiing for about 45 minutes, with Rickenbacker and Bartek hanging their legs over the front of the wing, they contacted PT boat 26 who was searching the area. The two healthier survivors were transferred to the PT boat, but Adamson, who was in no condition to be moved, stayed in the radioman’s seat for the remainder of the taxi ride. Boutte continued the trip spending about 8 hours in the wake of the prop wash sitting on the wing. They arrived back at the base about 0300 or 0400 hours the next morning.

All the survivors were suffering from exposure, sunburn, dehydration, and near starvation. Rickenbacker had lost 40 pounds (18 kg).

A US Navy PBY Catalina flown the survivors from Funafuti to the main base on Tutuila. Rickenbacker’s legs were so weak after three weeks at sea that he had to be lifted from the side machine gun blister of the Catalina.

Supported by USMC Colonel Robert L. Griffin, Jr. (left with pith helmet) and an unidentified Navy crewman, helped Rickenbacker from the Catalina on Samoa. Note his left hand and wrist is bandaged. Probably a slight breeze made Rickenbacker’s hair stand up.

On Samoa, Rickenbacker is smiling in a Jeep as he is driven away from the landing strip to get a meal of hot soup and ice cream. Note his left hand and wrist is bandaged and is holding a cigarette. The officer in the back seat is unidentified. Sources state that the Jeep driver in this photo is Colonel Griffin but in the above photo Griffin is older with a mustache and this younger marine does not have a mustache.

In December 1942, Rickenbacker (right) talking with Lieutenant Eadie (left) under the wing of a PBY Catalina. The officer between them is unidentified. Sadly, Eadie and his Kingfisher (not The Bug) was listed as MIA on 8 January 1945.

After his stay in the hospital on Samoa, Rickenbacker proceeded on his original mission, including inspections of facilities at Port Moresby, Guadalcanal, and Upola. He meet General MacArthur in Port Moresby and gave him the secret message. No one has ever divulged its contents. He reported to Secretary Stimson and General Arnold on December 19th, and then returned to New York the following day where he was reunited with his family.

B-24 Rackenbacker

Ford B-24E-5-FO Liberator (only 60 of this variant was built), s/n 42-7011, of the 34th Bomb Group, 391st Bomb Squadron had a “Hat in the Ring” emblem and Rickenbacker’s imagine as nose art. Rickenbacker signed “Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker Jan 22~1943” on the port (left) side of the bomber.

The B-24E named after Eddie Rickenbacker returned to the airfield at Ford’s big Willow Run plant in Michigan after a successful trial flight. The national insignia on the fuselage is correct for 1942.

This is a close up of the nose. At sometime, the bomber was repainted and they painted around the original nose art and Rickenbacker’s signature/date.

In 1943, the 34th Bomb Group was a training group based at Salinas Army Air Base in California (south of San Francisco along the west coast).

On 3 July 1943, B-24E “Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker” was burning fuel at an excessive rate prior to losing two engines over the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Santa Barbara. Pilot Thorel “Skip” Johnson ordered the crew into their parachutes and turned the bomber around, heading back towards Santa Barbara. Two airmen, Robert Prosser and Peter Dannhardt, not knowing they were still over water, bailed out prior to the pilot giving the order and were lost at sea. The remaining eight crewmen bailed out safely after the bomber had reached land over the mountains. The unmanned bomber crashed 9 miles (14.5 km) north of Santa Barbara. The crew’s next bomber, a Consolidated B-24D-105-CO Liberator, s/n 42-40837, was named “BOB ‘N PETE” for the two crewmen that were lost at sea.

In April 1944, the 34th Bomb Group was re-equipped with B-17s and assigned to the US 8th Air Force in the UK. It entered combat in May 1944.

Film: 1956 CAPTAIN EDDIE RICKENBACKER US WW1 ACE OF ACES SPEAKS

In 1960, Eastern Air Lines’s first jets, the Douglas DC-8-21 “Golden Falcon”s, were introduced on the longer flights like the non-stops from New York and Chicago to Miami. In December 1960, Eastern became the first airline to offer jet flights to West Palm Beach, Florida.

Rickenbacker points out the Golden Falcon title on one of Eastern’s DC-8-21 jets in October 1960.

On the last day of 1963, Rickenbacker retired as Eastern Air Lines Chairman of the Board, 45 years after his glory days over France in 1918.

A 1971 press photo of 81 year old Rickenbacker looking at a WWI German Fokker biplane replica at a museum in Milkwaukee, Wisconsin.

Today

Video: The American Heritage Museum’s 1918 Nieuport 28 – America’s First Fighter Returns to the Skies

A SPAD S.XIII in the markings of Captain Eddie Rickenbacker’s US 94th Aero Squadron at the National Museum of the US Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

On display at the National Air And Space Museum / Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. is the Comic Strip “Hall of Fame of the Air” by E.V. Rickenbacker and Clayton Knight and Featuring Blanche Stuart Scott.

Free Audio book: “Fighting the Flying Circus” by Eddie Rickenbacker

The printed book is still available.

Model Kits

1/16:

Model Airways MA1002 Nieuport 28 – 1917 Eddie Rickenbacker’s Airplane

1/28:

Revell 04730 WW I Fighter Aircraft SPAD XIII – 2007

1/32:

Roden 616 Nieuport 28 c.1 – 2008

Roden 636 SPAD XIII c.1 Late – 2022

1/48:

Roden 403 Nieuport 28C1 – 2004

Eduard 1142 Spad XIII American Eagles Dual Combo – 2009

1/72:

Revell 04113 SPAD XIII C-1 – 1992

Revell 04189 Nieuport N.28 C-1 – 2008

Hippo Models RK-701 German WWI Ballon Drachen 1917 (Resin Kit)